The brains of teenage girls aged more rapidly during the pandemic, study shows

The brains of teenage girls aged faster during the pandemic, a new study concluded. The paper was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

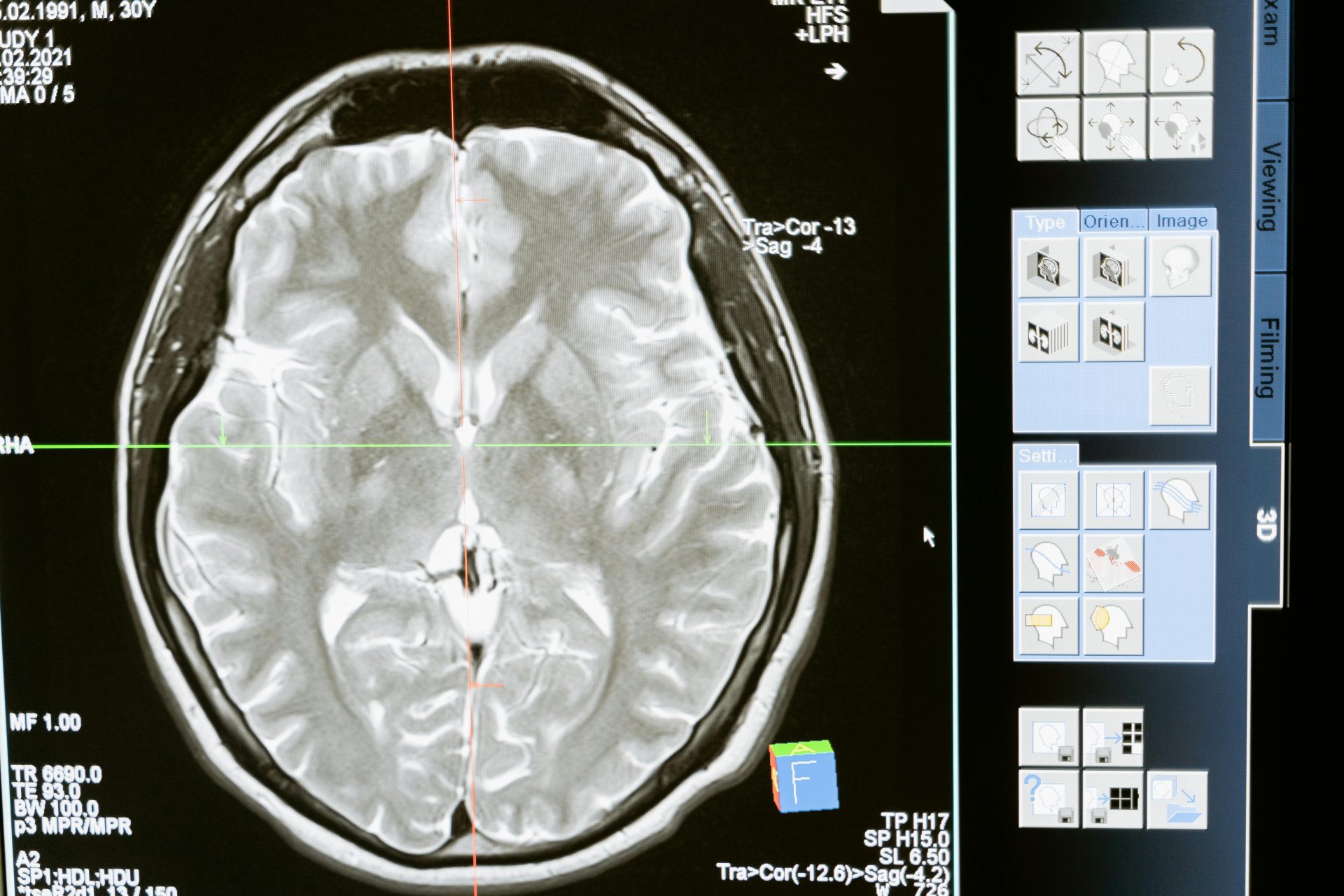

University of Washington researchers started scanning teenagers' brains in 2018 for a development study. They tested 160 individuals, but in 2020, the pandemic interrupted their work.

That allowed them to collect scans of teenagers' brains before and after lockdowns. Neva Corrigan, the study's lead author, described it to the New York Times as "a natural experiment."

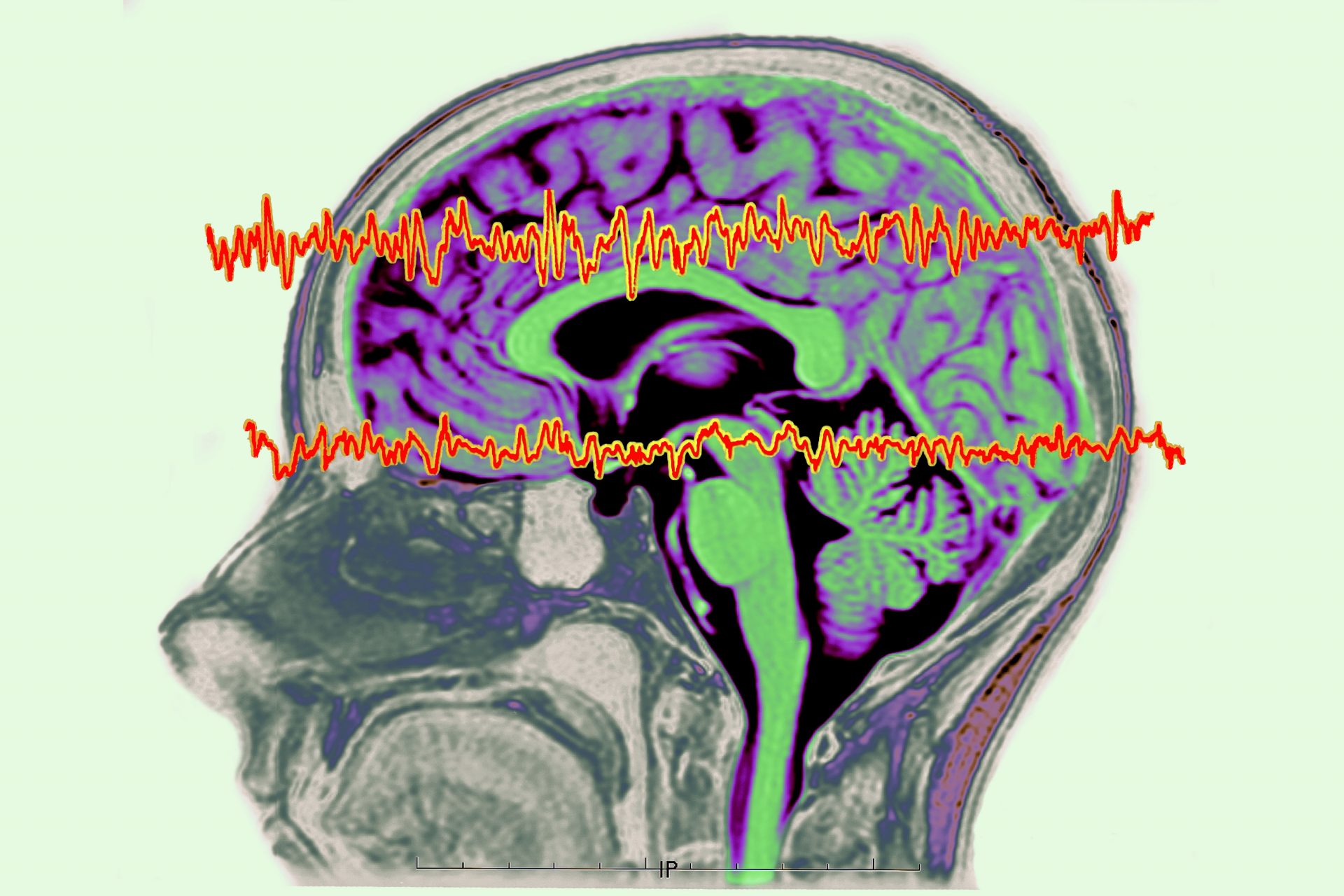

After the pandemic lockdowns, more than 130 teenagers came back for brain scans. The team discovered that their brain cortex had thinned faster than the average rate.

Cortical thinning is a normal process that occurs as teenagers transition to adulthood. It starts in late childhood as the brain shrinks its outer layer to eliminate redundant processes.

Photo: Mart Production / Pexels

According to the NY Times, some experts view the process as the brain rewiring itself to increase efficiency as it matures. So it is simply a part of growing up.

However, what the team found in the post-pandemic teenage brains is accelerated thinning, which has been correlated with cases of depression and anxiety. The subjects' brains matured much faster than usual.

The researchers could also compare the teenagers' brain scare by gender. They discovered girls' brains developed much faster than their counterparts during lockdown.

According to the NY Times, the study concluded that, on average, teenage girls' brains aged 4.2 years, while boys' aged 1.4. Girls' cortex thinned nearly three times faster.

"A girl who came in at 11 and then returned to the lab at age 14 now has a brain that looks like an 18-year-old's," Patricia K. Kuhl, one of the study's authors, told the NY Times.

The authors attributed the accelerated thinning in girls' cortex to social deprivation. Dr. Kuhl told the newspaper that girls depend more on social interactions and talking with friends.

The team also found fast thinning all over the girls' brains and only in some areas of the boys'. Still, she clarified that it is vital not to pathologize the accelerated development. It is not a sign of brain damage.

Many studies have explored the effects of the pandemic on the mental health and development of children and teenagers. However, the University of Washington study is the first to present physical evidence.

Still, other researchers are not entirely convinced of the study's efficacy. Bradley S. Peterson, a pediatric psychiatrist at Children's Hospital in Los Angeles, told the NY Times that the paper had many flaws.

Dr. Peterson, who was not involved in the study, said the main concern was that the data from before and after did not come from the same subjects, so it is not a picture of brain evolution.

He also pointed out the researchers did not have enough evidence to suggest that social isolation was the reason behind the accelerated thinning, rather than any other pandemic issue like stress or increased screen time.

He did agree that if the accelerated development did occur, it was simply the brain's adaptation to the complex circumstances of the pandemic, not brain damage.

More for you

Top Stories