The UN hopes to curve a global health crisis by 2030

Global health officials gathered on September 26 for a high-level meeting to discuss antimicrobial resistance, a health crisis that costs millions of lives yearly. They made some pretty significant commitments.

International officials agreed to reduce deaths related to antimicrobial resistance by 10% before 2030 and ensure that every country has a plan to tackle the issue.

However, according to The New York Times, as health officials gather, some of them are trying to change the scope of the problem to prevent more deaths, especially in developing nations.

The issue around antibiotics is that some populations have accessed them excessively while others have struggled to obtain them. According to the newspaper, some experts hope to move from resistance to entitlement.

In The Lancet, economist and epidemiologist Dr. Ramanan Laxminarayan said that experts should work toward guaranteeing everyone access to an effective antibiotic, no matter the infection.

That way, he said, the concern would become more simple for the public to understand while experts tackle the lack of antibiotics in the developing world and pursue the reason behind antimicrobial resistance.

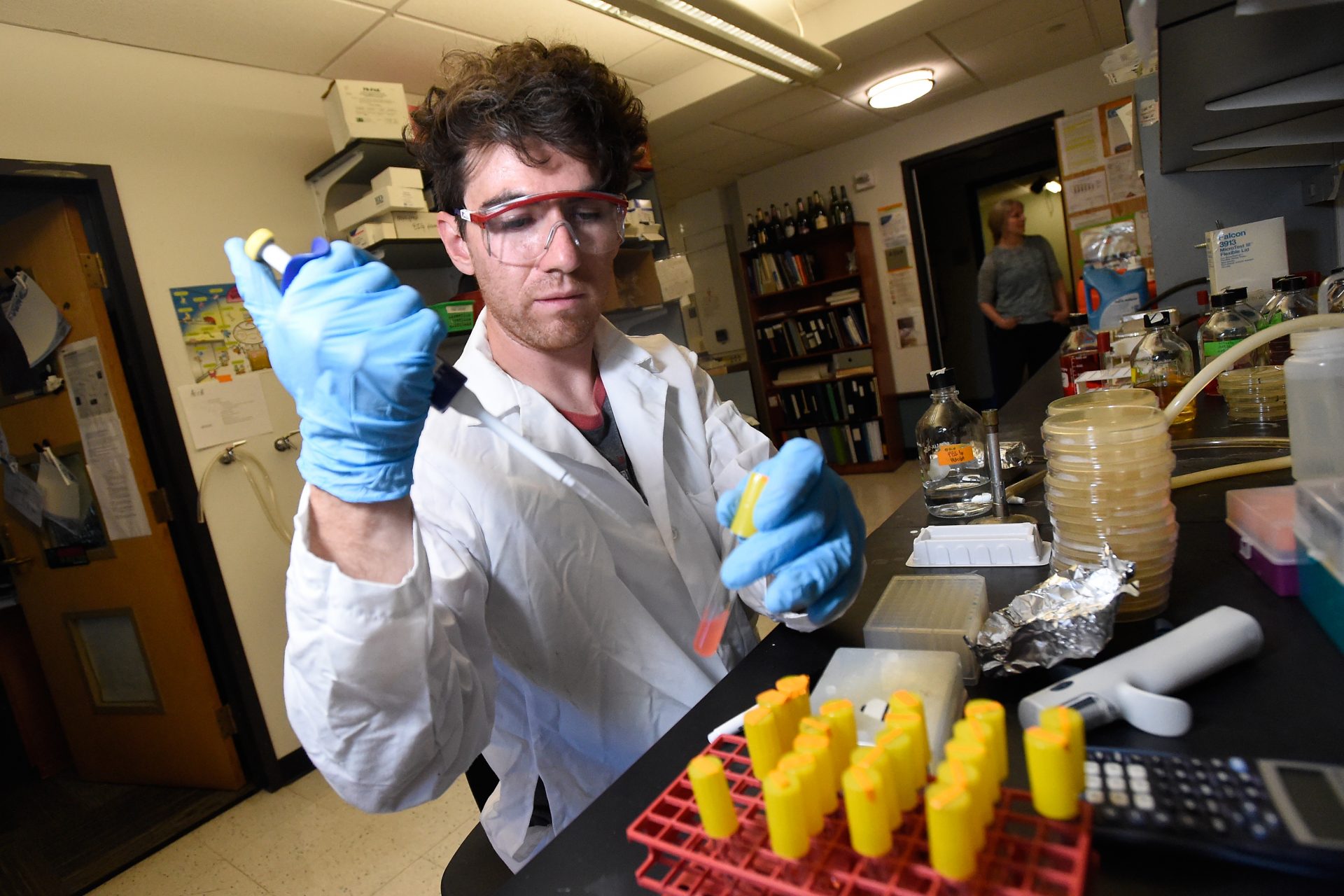

In the developed world, the cause is that antibiotics are so commonly used that some bacteria developed resistance to it. A new class of antibiotics has also provided science with the hope of tackling it.

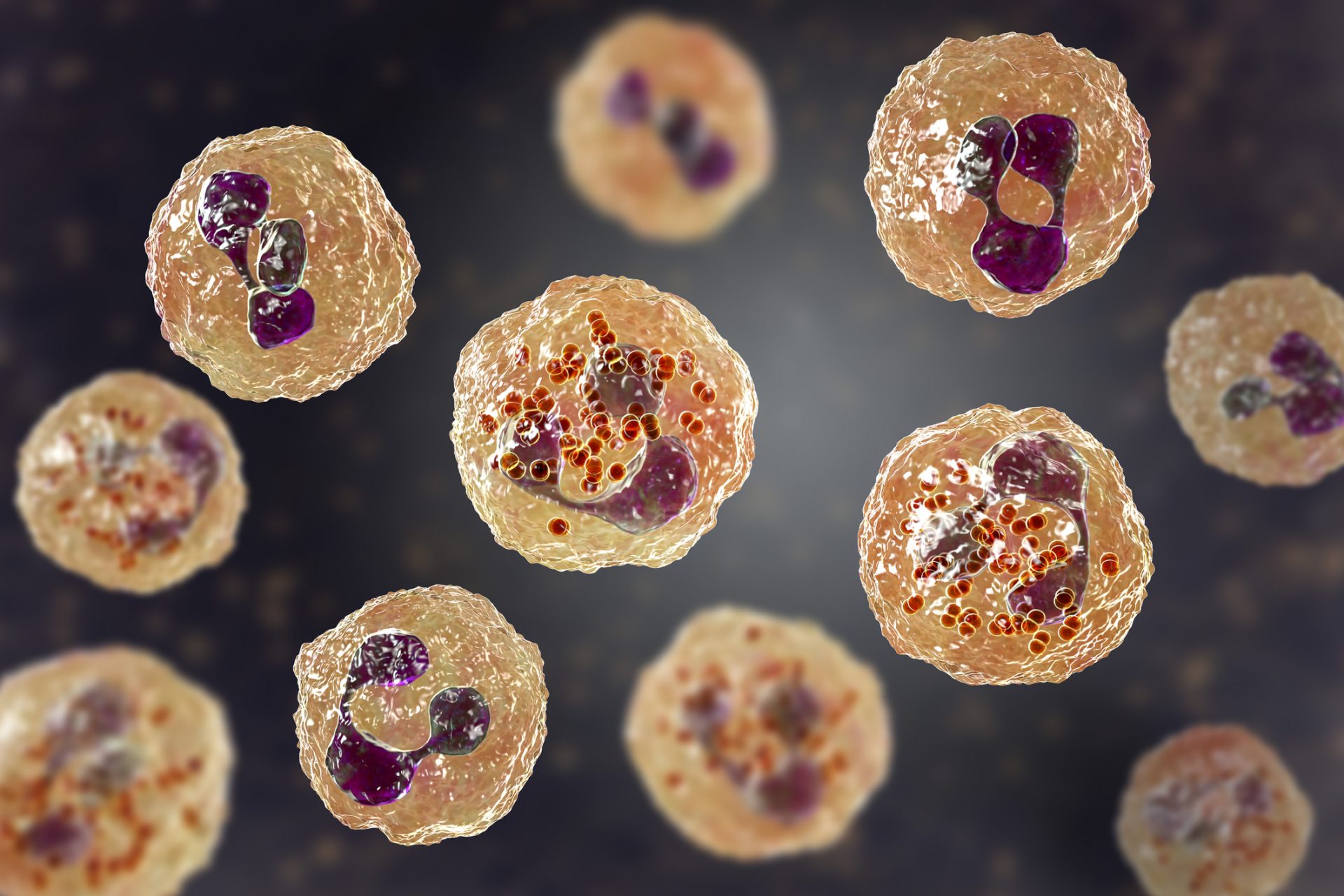

According to a study in Nature, the new substance, Zosurabalpin, was effective against highly resistant bacteria in mouse pneumonia and sepsis cases.

The Guardian reported that the bacteria Zosurabalpin killed was one of the top three bacteria considered to pose the greatest risk for humanity.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (Crab) as a top-priority critical pathogen alongside two other resistant bacteria.

Dr Andrew Edwards, a senior lecturer in molecular microbiology at Imperial College London, told The Guardian that Crab causes infection in hospitals, primarily through ventilators.

Hospitals are a breeding ground for many resistant germs. According to the CDC, staying in a healthcare facility puts you at risk of getting an antibiotic-resistant infection.

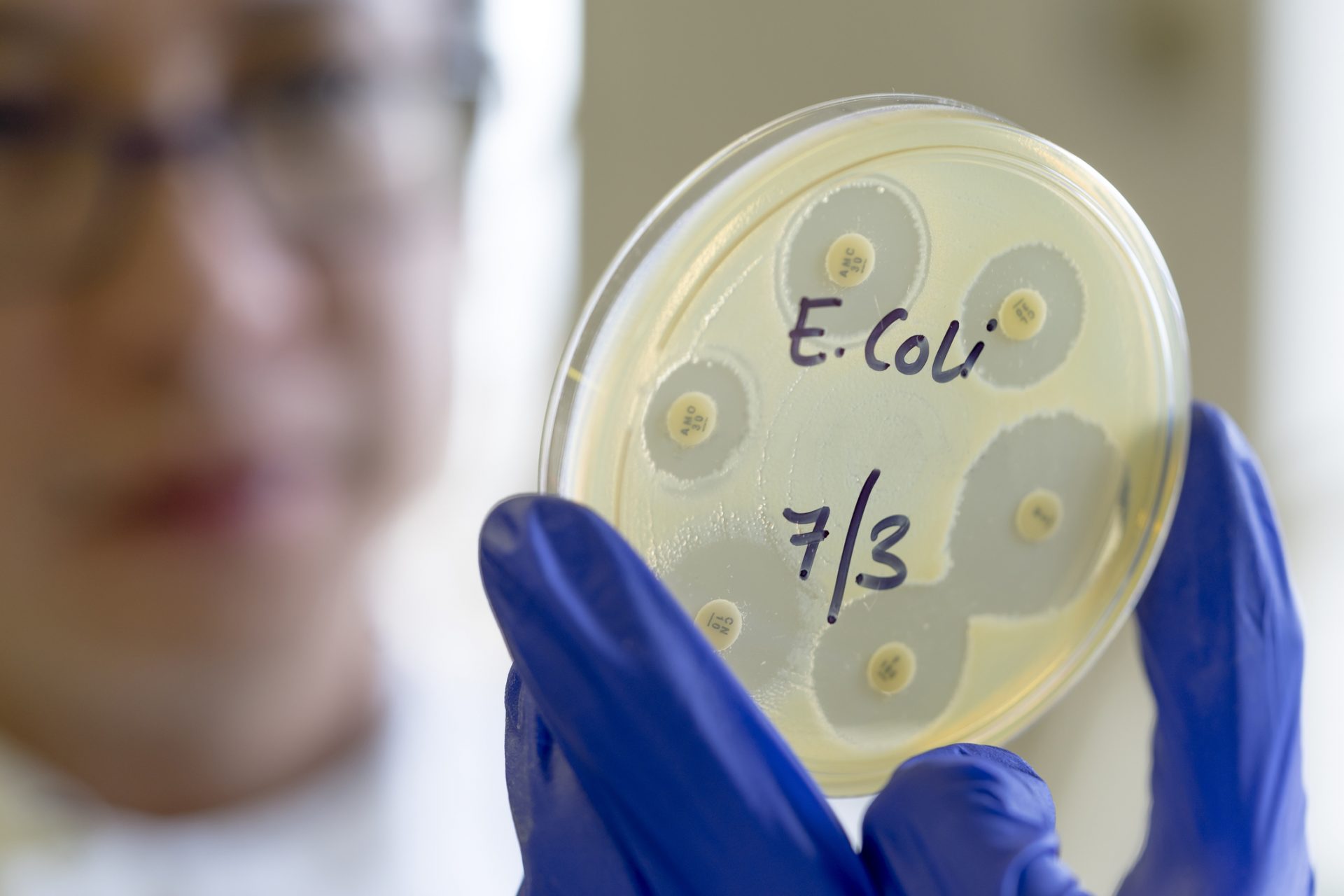

Gram-negative bacteria are the most risky bacteria in healthcare settings. They can cause pneumonia, bloodstream infections, wound or surgical site infections, and meningitis.

The CDC claims gram-negative bacteria are increasingly resistant to most available antibiotics. They have an outer layer protecting them and can quickly adapt to fight antibiotics.

Worldwide, according to the WHO, 1.2 million people have died from a confirmed drug-resistant infection in 2019. These germs were also partially responsible for 5 million deaths.

The WHO and the CDC have warned that antimicrobial resistance is an urgent global public health threat. It also threatens many medical procedures.

Antimicrobial resistance profoundly affects medical personnel's ability to treat infections and extends patients' risks of side effects and other illnesses.

It can also damage other medical treatments that depend on our capacity to avoid infections, like surgery, transplants, cancer therapy, and the treatment of chronic diseases.

Zosurabalpin's development is promising because it provides a new approach to drug discovery. It affects germs differently than previous antibiotics.

According to The Guardian, the new drug focuses on the LPS barrier that allows gram-negative bacteria to live in any environment and easily resist antibiotics.

Specifically, Zosurabalpin prevents the substance from being transported to the outer layer of the bacterium, killing it and reducing the infection.

The newspaper cited experts who spoke about other drugs in development that also tackle the LPS barrier, which could begin a new phase in the battle against antimicrobial resistance.

More for you

Top Stories