A global problem: how Europe deals with immigration

According to the European Commission, out of nearly 450 million inhabitants, the European Union (EU) had 27.3 million non-European citizens on its territory, or around 6% of its population.

The EU's migration balance is positive every year, which means it receives more people than the ones who leave. In 2022, the difference exceeded 1 million people due to the influx of Ukrainian refugees.

Most of that migration is related to asylum requests. The 1951 Geneva Convention provided an internationally valid definition of refugee status.

The treaty states that a refugee is “any person with a well-founded fear of being persecuted because of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a certain social group or political opinion, is outside the country of which she has a nationality.”

Beyond political persecution, many reasons can push individuals to leave for another country: war, lack of economic opportunities, or even unsustainable environmental conditions.

Photo: Julie Ricard / Unsplash

Asylum requests are on the rise in Europe: 1,142,618 people filled requests in 2023 in the 27 member states, Norway and Switzerland, according to the European Union Agency for Asylum. It was 18% more than in 2022.

According to the same agency, Syria is the most represented country among applicants (16%), followed by Afghanistan (10%) and Turkey (9%). 4.4 million Ukrainians also benefit from temporary protection since the invasion of their country in 2022.

Photo: engin akyurt / Unsplash

Germany is the Member State with the most requests (29%), followed by France (15%), Spain (14%) and Italy (12%). 43% of requests were recognized, the highest rate in seven years.

The EU has had a standard migration policy since the 90s. It regulates the free movement of nationals within the Schengen area and defines conditions for immigration.

Photo: Christian Lue / Unsplash

As for the specific case of asylum, the Dublin III regulation determines which Member State is responsible for examining an application: this is generally the country of entry, the first in which the person arrived.

Photo: Eric Masur / Unsplash

The Common European Asylum System (CEAS) sets minimum standards for treating asylum seekers. But, in practice, the conditions and rate of application acceptance vary from state to state.

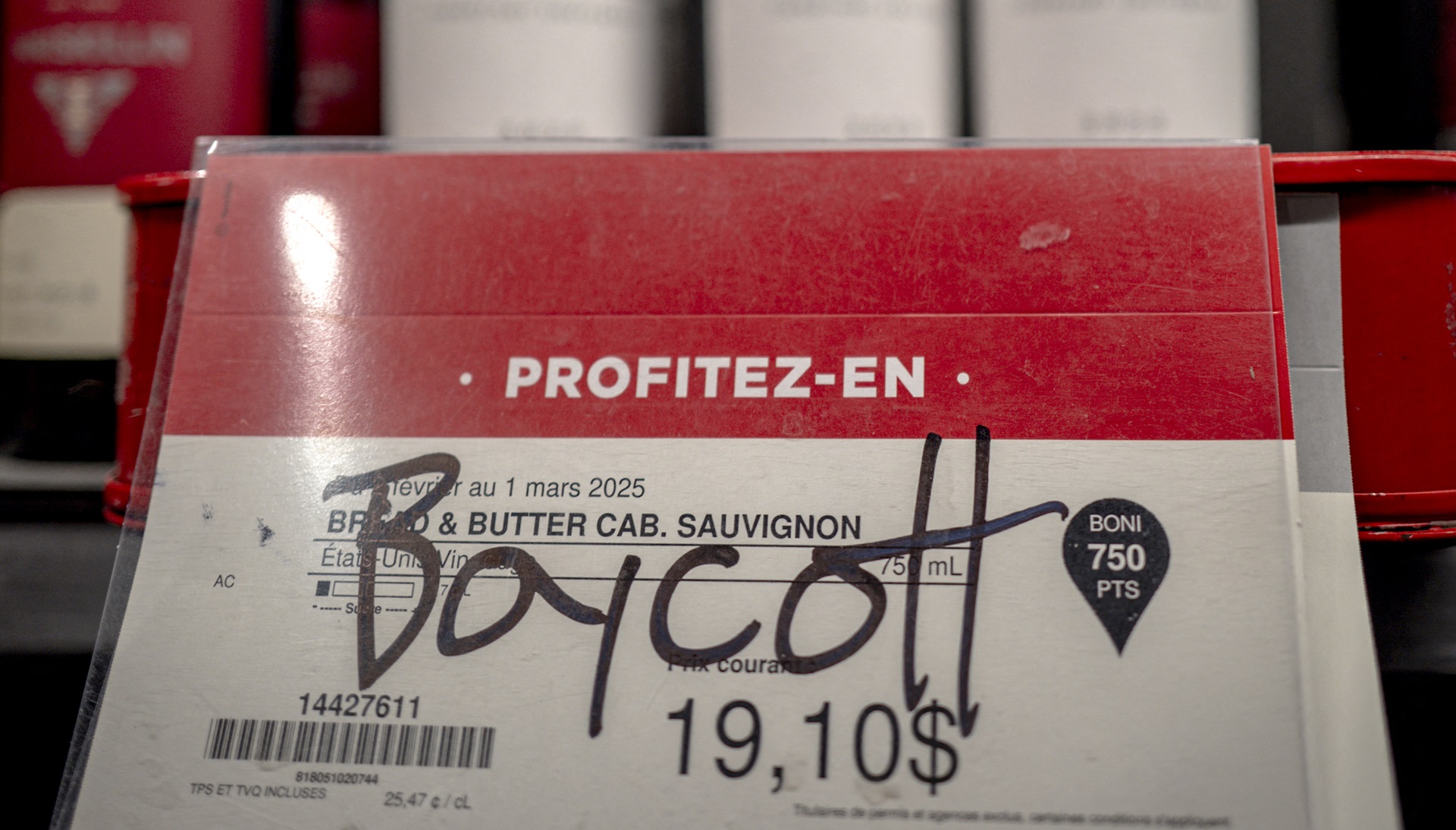

According to the European Council website, this leads to an “asylum race,” in which applicants move from one country to another in the hope of finding better conditions.

However, the journey of migrants arriving in European territory often takes place in chaotic conditions.

Many refugees wish to reach northern Europe, but the Dublin Regulation requires them to stay in the first state they get to, most often Italy or other southern countries, due to the Mediterranean crossing.

"Stuck at the border, these men, women, and children must wait for their residence permit to be issued or risk crossing into other European countries illegally," National Geographic explains.

Migrants generally benefit from health care in the host countries, thanks to public health systems, but it still depends on each nation.

However, an OECD report noted that care for the psychological aftereffects of an uncertain and dangerous journey remains insufficient in Europe.

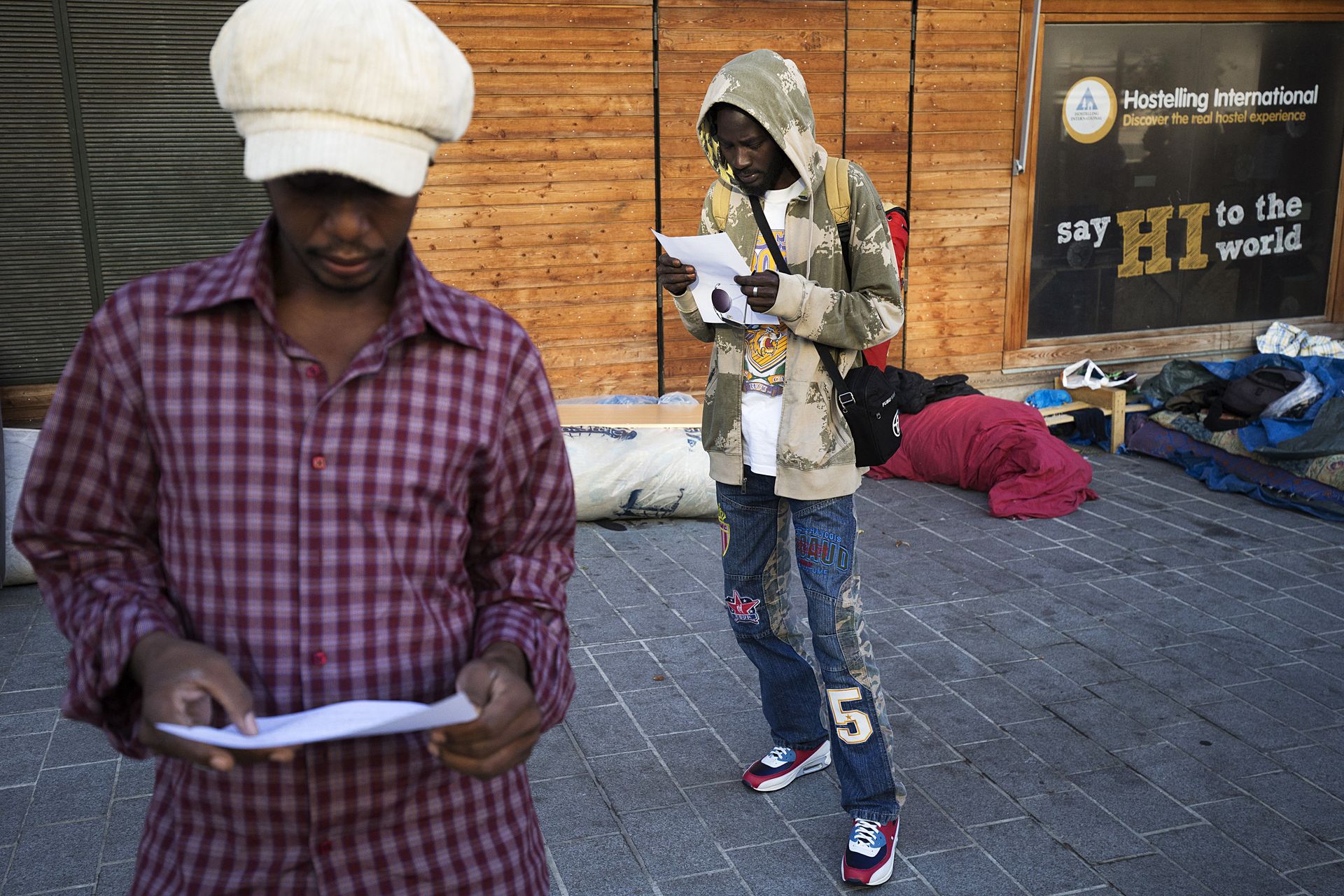

National Geographic published a feature about Senegalese migrants who sheltered in a prison in the Amsterdam suburbs. "The important thing is that we are safe," said one woman when asked about their accommodation.

According to National Geographic, most countries must offer beds, meals, and temporary shelter to migrants seeking citizenship and a job.

Still, citizens often aid migrants due to a lack of public funds. For example, the Refugees Welcome Association connects asylum seekers with host families in France. Similar initiatives exist in other countries.

In the same country, migrants, including many unaccompanied minors, can benefit from help from associations such as the Fondation de France.

The Foundation offers psychological support to people who need it, supports civic engagement by training volunteers to learn French, and provides legal aid.

The question of legal aid is precisely one of the most delicate. Still, according to the European Fundamental Rights Agency, most countries provide some assistance to migrants.

Associations also help refugees and migrants assert their rights, particularly regarding accommodation in reception centers and asylum seeker allowance.

After the 2015 migration crisis, when Europe received over 1.4 million refugees, the EU designed a system for receiving countries, like Italy, to drogue some of the required procedures or request aid for social assistance.

Almost ten years after the refugee crisis of 2015, the question of welcoming migrants remains a burning issue in Europe.

More for you

Top Stories