A NY police officer killed a teenager with a mental health issues

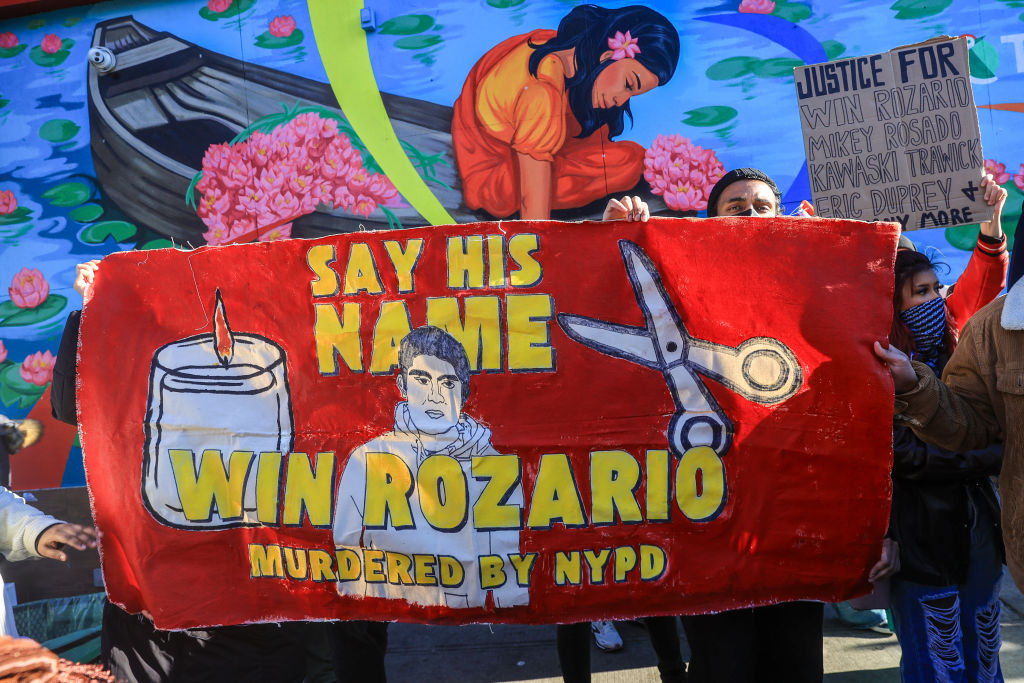

On March 27, 2024, Win Rozario, a 19 year old teenager called 911 because he was having a mental health crisis. When NYPD officers arrived at his house, Rozario came at them with kitchen scissors so they shot him, NY Daily News reported.

Civil rights attorney Joel Berger, who spent nearly a decade monitoring police misconduct, told the outlet that it “doesn’t add up.” “Two cops ought to be able to disarm or at least resolve the situation without having to shoot the kid dead,” he added. “It’s a household pair of scissors.”

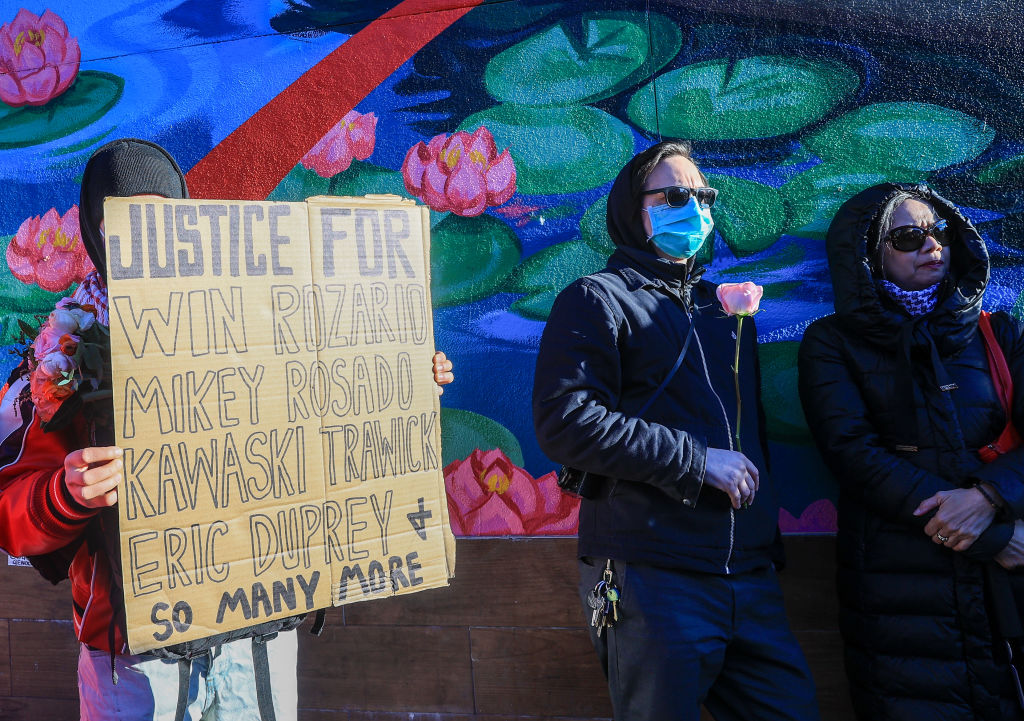

But the incident, that’s sparked a lot of public outrage, is hardly the first one of its kind. According to New York Lawyers of the Public Interest, it is the 20th killing of a mentally ill person by police in the city since 2015, a number that doesn’t include those who’ve been injured or arrested.

And it is not only a New York problem, it happens across the United States. Those that suffer from mental illness or are differently abled are particularly vulnerable to police violence.

People with an untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than other civilians approached or stopped by law enforcement, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center.

This, according to a Washington Post database of fatal U.S. shootings by on-duty police officers. Since 2015, when The Post launched its database, police have fatally shot more than 1,400 people with mental illnesses.

Almost half of the people who die at the hands of police have some kind of disability, according to a report published by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a disability organization.

Angela Kimball, national director of advocacy and public policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, said she believes the numbers are so high because people in mental health crises do not always respond in ways officers want them to.

Haben Girma, a lawyer and activist who has a hearing and a visual impairment, told TIME: “Someone might be yelling for me to do something and I don’t hear. And then they assume that I’m a threat.”

Coverage of police brutality cases has understandably focused on race, but that lens can also obscure how disability and mental health problems also factor into police interactions.

In 2014 a black teenager was killed by the police while acting erratically and holding a knife. Prosecutors charged an officer with first-degree murder, noting McDonald did not pose a lethal threat to the officers who had surrounded him.

When the video of the shooting was released, it sparked the resignation of Chicago’s police chief and a national debate over race and policing. There was far less focus, however, on McDonald’s health.

According to a later investigation by the Chicago Tribune, McDonald suffered from PTSD and “complex mental health problems.”

Black people are more likely than white people to have chronic health conditions, more likely to struggle when accessing mental-health care and less likely to receive formal diagnoses for a range of disabilities, according to the CDC.

Have lower incomes than white Americans and live in less safe neighborhoods. These factors contribute to worse mental health outcomes.

A 2016 report from the Police Executive Research Forum found that nationwide, police academies spend a median of 58 hours on firearm training and just eight hours on de-escalation or crisis intervention.

Crisis-intervention training, which is designed to help officers safely and calmly interact with people with disabilities and de-escalate confrontations with the mentally ill.

Arc, one of the United States’ largest disability-rights organizations has a program to teach law-enforcement officers, lawyers, victim-services providers and other criminal-justice professionals how to identify, interact with and accommodate people with disabilities.

Hamilton Police Service's new Mental Health Crisis Response Training Program uses virtual reality to help teach police officers to recognize the signs of a mental health crisis and improve how they de-escalate situations.

But as seen in Rozario’s case and others, police interventions can make health crises worse. For instance, there was a case of a woman in Tempe, Arizona who called the police because her 29-year-old son, who had bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, was experiencing a manic episode.

The woman needed help getting him to a mental health facility. But when police showed up at her apartment with riot shields and rifles, they all panicked, including the son, the officers were yelling, and the situation quickly escalated.

Tempe Police Chief Sylvia Moir told TIME that we have to first consider this question: “Is the police the right societal actor to be inserted into this space and into this societal issue?”

CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets), is a program that reroutes 911 and non-emergency calls relating to mental health, substance use or homelessness to a team of medics and crisis-care workers. Those teams respond to such calls instead of the police.

In New York, a similar program exists, called the Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division, or B-HEARD. However, due to budget cuts, it only serves in 31 precincts, and the place where Rozario lived and was killed was not included.

Still, some people call the police because social stigma leads to a perception of people with a mental illness as being violent and dangerous. Nevertheless, according to the American Psychiatric Association, most people with mental illnesses are not violent, and using law enforcement as a blunt instrument contributes to the stigma that they are.

In fact, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) people with a mental illness are much more likely to be victims of a crime than to commit one, as they are a vulnerable group of society.

More for you

Top Stories