Rising seas aren't the only concerning consequences of climate change

Some of the most concerning consequences of modern climate change are often overlooked when scientists and policymakers discuss the disasters a warming world will wreak on our planet. But there are many other things we should be worrying about.

Massive lakes are bubbling with methane, ice-rich ground is collapsing under the weight of increasingly hotter temperatures, and ‘zombie fires’ are smoldering underground for months at a time as the world's climate changes and gets warmer every year, especially in the Arctic.

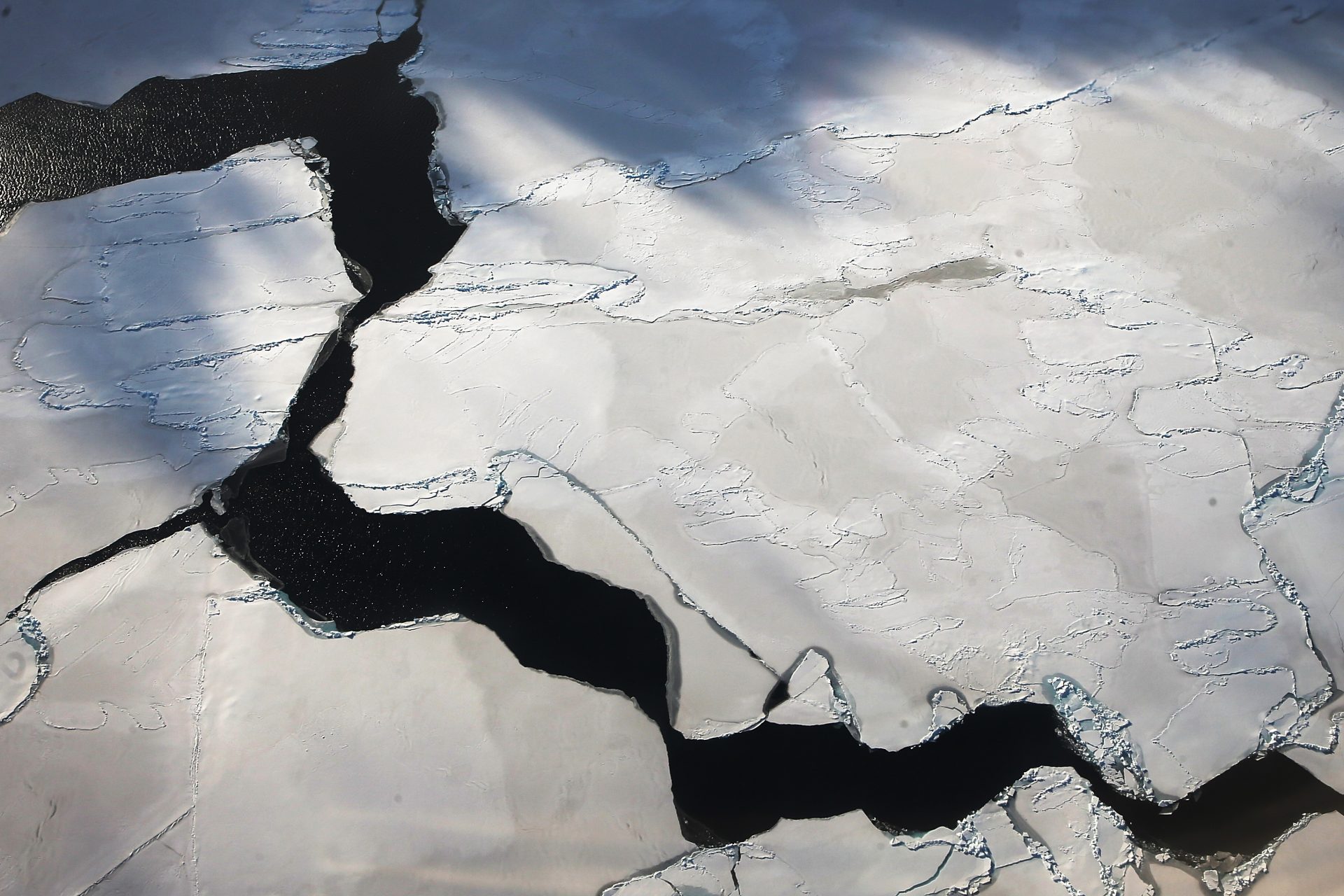

Hotter Arctic temperatures aren’t a surprise to scientists. This region of the world has been getting warmer four times faster than the global average, weakening the top layer of Arctic permafrost.

Melting Arctic permafrost is one of the least understood aspects of today’s climate change crisis, especially in places like Alaska, Canada, and Siberia where layers of permafrost have long acted as a giant freezer—locking in soil and potentially deadly organic matter.

The most obvious problem that could be caused by the worrying threat of melting permafrost comes from the release of ever-increasing levels of carbon and methane gas into the Earth’s atmosphere.

“Permafrost is like the dirty cousin to the ice sheets,” Merritt Turetsky, director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado Boulder said according to a 2022 CNN report on the world's rapidly melting permafrost. “It’s a buried phenomenon.”

“You don’t see it. It’s covered by vegetation and soil. But it’s down there. We know it’s there. And it has an equally important impact on the global climate.”

The northernmost reaches of the planet are home to about 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon, roughly 51 times the amount the world currently released in 2019, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

“We’re just talking about a massive amount of carbon,” Brenda Rogers, an associate scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts, told CNN.

“We don’t expect all of it to thaw … because some of it is very deep and would take hundreds or thousands of years,” Rogers said, “But even if a small fraction of that does get admitted to the atmosphere, that’s a big deal.”

All of this formally captured carbon is starting to make its way to Earth’s surface and is also causing some previously unknown geological phenomena to occur.

There has been a sudden appearance of about 20 perfectly calendrical craters in Siberia’s remote northern communities over the past ten years.

Dozens of meters in diameter, scientists believe these craters are the result of explosions of built-up methane gas under the Earth’s surface.

“The Arctic is warming so fast,” said Rogers, “and there’s crazy things happening.”

One of the most fascinating consequences of thawing permafrost is the intense wildfires the situation has caused all across Siberia, as well as the underground fires that sometimes smolder for months after the fires above ground have been extinguished.

Nicknamed ‘zombie fires’ by the scientists who study them, these blazes are becoming an increasingly big contributor to the world's climate crisis.

“The fires themselves will burn part of the active layer [of permafrost] combusting the soil and releasing greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide,” Rogers said.

“But that soil that’s been combusted was also insulating, keeping the permafrost cool in summer. Once you get rid of it, you get very quickly much deeper active layers, and that can lead to larger emissions over the following decades.” Rogers continued.

Not only will rapid thaws release more carbon into the atmosphere, but they will also pose a serious risk to global health.

Long-dormant microbes that have been trapped under the frozen permafrost for thousands of years are beginning to wake as the Arctic warms, unlocking ancient diseases.

Back in 2016, an outbreak of Anthrax in Siberia that sickened 72 people and killed a 12-year-old boy was linked to thawing permafrost in the area.

Bacteria from thawing human and animal remains that date back thousands of years ago can also get into the groundwater that people drink.

Jean Michel Claverie, a genomics researcher specializing in ancient viruses and bacteria, believes modern society is likely to come into contact with more ancient diseases as the permafrost thaws.

“We could actually catch a disease from a Neanderthal’s remains,” Claverie explained to Vox in 2017. “Which is amazing.”

Claverie also said he saw no reason why some long-lost human infections couldn’t emerge from the ice and thrive in a new age where humans have lost their immune defense against them.

As temperatures warm, and northern soils become more accessible, governments and businesses are likely to tap into the newly available resources of Arctic land—something that would almost certainly put humans into contact with very old bugs and diseases.

Also deeply concerning is how thawing permafrost will change our current typography. Communities in Alaska are already seeing the effects of a warmer climate.

Nunapitchuk, a remote Alaskan community, has been sinking into the ground since 1969 and is currently being swallowed by boggy marshes.

“The bogs are showing up in between houses, all over our community,” said former resident Morris J. Alexie according to CNN. “There are currently seven houses that are occupied but very slanted and sinking into the ground as we speak.”

“Everywhere is bogging up… It’s like little polka dots of tundra land. We used to have regular grass all over our community. Now it’s changed into a constant water marsh.”

At present, there is no solution to the thawing problem. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projects that if the world reduces emissions by 50 percent before 2030, we’re likely to only see a 1.5 Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) increase in the global temperature.

While a 1.5 Celsius increase in global temperature may seem small, it is still more than enough to trigger melting that cannot be undone or reversed. “It is basically impossible to grow back permafrost under rising temperatures,” the ICPP concluded.

More for you

Top Stories