Are Americans getting meaner?

It’s a question that has been posed around many household tables, as well as in major news outlets in recent years, from the New York Times to The Atlantic. While there is no single measure of “meanness,” some evidence points to a solid trend.

In 2023, the FBI reported that the number of hate crimes in the US had reached an all-time high in 2022, with 11,288 reported incidents. The FBI began collecting data on this in 1991, and incidents have steadily risen, though it may also be a matter of reporting.

According to Giving USA, Americans gave 1.7% of their personal disposable income to charity in 2022, which is the lowest level since 1995. Back in 2007, that number was at 2.2%.

Unsurprisingly, hostility has been growing between Republicans and Democrats. According to Pew, growing shares of each faction view the other side as significantly more closed-minded, dishonest, immoral, lazy, and unintelligent now than they did in even 2016.

In the US, the General Social Survey has been gathering information on trust attitudes since 1972. It has found a downward trend in people agreeing with the statement “most people can be trusted.” In the 1970s and early 80s, at least 40% agreed, reaching a high of 49%. But that number has dropped to the low 30% figures since 2010.

A study led by Sara H. Konrath at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor found that self-reported empathy has declined since 1980, with an especially steep drop after the millennium. In 2011, she found that almost 75% of students then rated themselves as LESS empathetic than the average student 30 years prior.

The Youth Right Now survey, published in 2023, found that 40% of youth said they were bullied on school property over the past year. That's 14% higher than in 2019. Experts suggested its a way of coping with the stress of the pandemic.

You may have heard about the man who punched a flight attendant, knocking out two of her teeth, on a flight in 2021. Well, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) had to implement a “zero tolerance” policy that year and begin fining people due to a huge spike in unruly behavior. In 2017, there were 544 incidents. In 2021, that number hit nearly 6,000!

While not exactly an evaluation of “meanness,” mental health is generally declining in the US. As of late 2022, just 31% considered their mental health “excellent,” down from 43% two decades earlier, according to Time Magazine. And the rate of people taking their own lives has increased by 30% since 2000.

Konrath of the University of Michigan theorized that social isolation may be exacerbating a lack of empathy. People are more likely to live alone and less likely to belong to groups. Other research has found that socially isolated people evaluate others less generously and are more likely to take advantage of others’ trust to cheat in an experiment.

To add more evidence to the social isolation theory, a 2018 Ipsos poll found that 54% of Americans report feeling like no one knows them well at least sometimes. Further, according to David Brooks in the Atlantic, the percentage of people who say they don’t have any close friends has increased fourfold since 1990.

Columnist David Brooks speculates that Americans have gotten meaner because politics are dominating identities. He points to research showing lonely young people are seven times more likely to say they are active in politics than non-lonely peers. But that politics today is more about tribalism… and doesn’t fill the void of meaning people may have in their lives, though it does make them angry.

A study conducted by the University of Toronto suggests reading fiction books might be linked to empathy in both children and adults. With the advent of new technology, people are more distracted and have less time to read. A 2023 survey by the National Endowment for the Arts found that 37.6% of Americans had read literature in 2022 versus 45.2% in 2012.

Sociology professor Charles Adeyanju said while the difference between pre- and post-COVID kindness may be sometimes overstated, he described the pandemic as the “gasoline” on the fire of meanness. This may have been because of “othering” people who broke strict pandemic rules or the massive polarization over some of the measures.

Brooks also points to a lack of moral formation in modern societies. Moral education programs in places like churches, schools, and groups like Boy or Girl Scouts faded away with new intellectual currents in the second half of the 21st century. “In a culture devoid of moral education, generations grow up in a morally inarticulate, self-referential world,” he wrote in the Atlantic.

He sums up his argument like this: “We inhabit a society in which people are no longer trained in how to treat others with kindness and consideration. Our society has become one in which people feel licensed to give their selfishness free rein. In a healthy society, a web of institutions—families, schools, religious groups, community organizations, and workplaces—helps form people into kind and responsible citizens.”

On the Gray Area podcast, Brooks also said that he thinks social media plays a role. “I think we’ve drifted into a world where we’re always broadcasting and social media is about how I’m broadcasting, but it’s not about listening, it’s not about taking the time to get to know another human story and making them feel seen, heard, and understood,” he said.

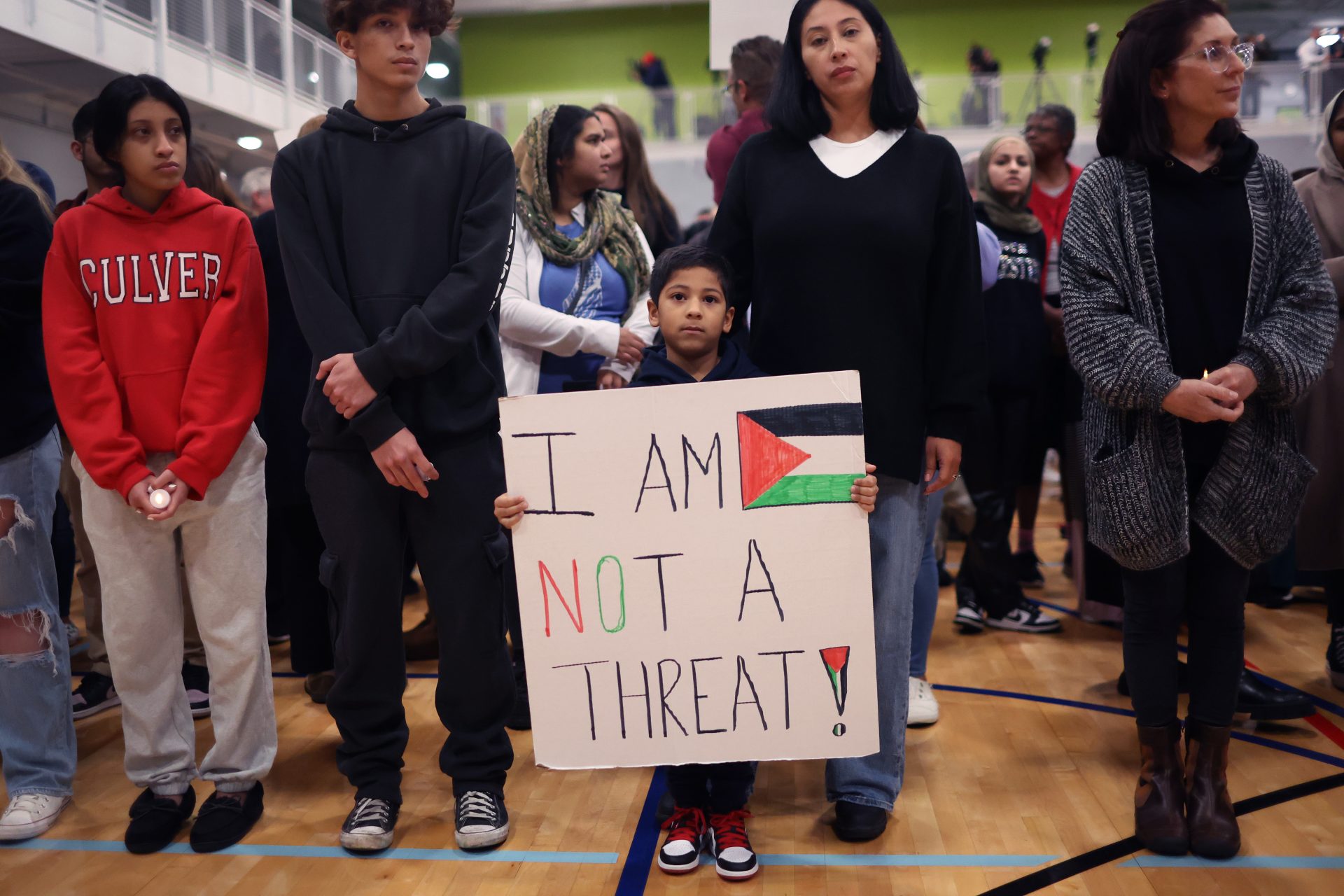

Journalist David Corn highlighted what he called a blind spot in Brooks’ explanation— mean political leaders. And yes, he’s referring to mostly Republicans and specifically Donald Trump and how they have “dehumanized” political foes. “Within the Republican cosmos, his meanness is a feature, not a bug,” he writes. “Trump spreads incivility, disrespect, hysteria, and paranoia. His inflammatory language—his racism and xenophobia—has inspired many and even led to bullying in schools.”

More for you

Top Stories