Can mRNA vaccines give us superhuman immunities?

Few people outside of those in the medical field likely knew about the big advances that were being made in vaccine technology when the coronavirus pandemic took over the world in 2020. But it was new technology that would save lives.

Vastly different from what had come before them, the mRNA vaccines proved to be just the right solution at just the right time since they helped protect the world from the worst the pandemic had to offer. But that was only just the start.

The vaccines that saved the world could also be used to turn humans into superheroes, but not in the way that you think. Vaccines based on mRNA technology could become a base used to change the way we deal with medical issues.

“It's such a game changer that it raises some very big, exciting questions,” Tim Smeadly of BBC News explained, adding that the technology might be useful in finding a cure for cancer, and could help us reach “superhuman immunity.”

Smedley's claim seems like a bold one. But if you understand how the technology works then it becomes a lot easier to understand how mRNA, short for messenger ribonucleic acid, vaccines could help humanity in the near future.

First, let’s look at how traditional vaccines work. Most traditional vaccines contain a core of DNA or mRNA that is wrapped in a protein that has been made to protect against one type of infectious agent according to Dr. Anthony Komaroff.

Dr. Komaroff was the Editor-in-Chief of the Harvard Health Letter when he explained in an article the exciting future of mRNA vaccines, noting traditional vaccines were made to teach the immune system to recognize and attack a problem.

Some traditional vaccines accomplish their goal through the use of a weakened form of a virus while others use a “critical piece of the virus’s protein coat.” However, vaccines made in this way have one big flaw: they take a long time to develop.

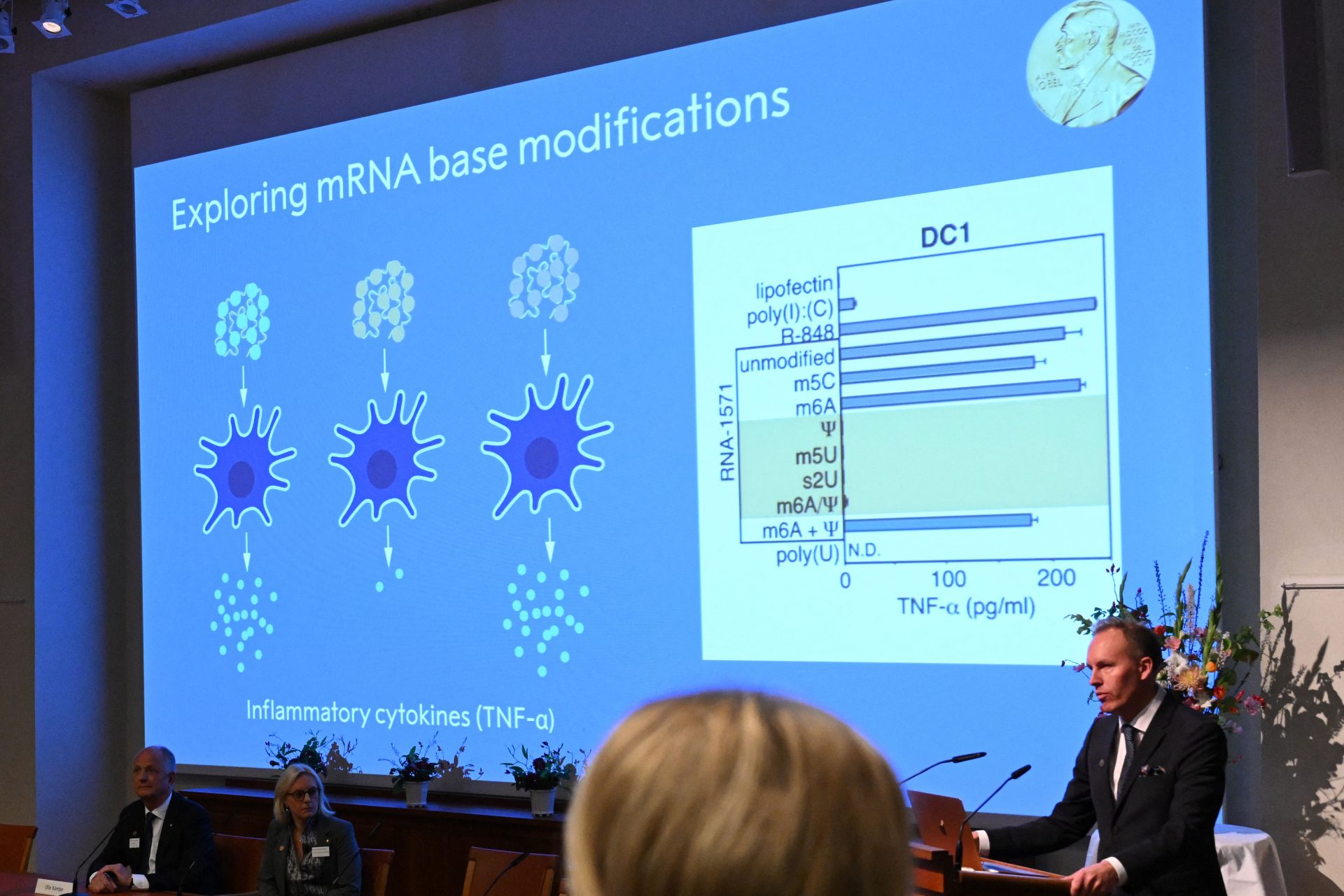

Roughly thirty years ago, researchers began looking at new ways to make vaccines and one method they came up with was the concept of teaching the body to make a virus so that a person’s immune system could also recognize the virus.

“How could you do that? First, you would need to make the mRNA. Second, you'd have to inject mRNA into the body and then get it into the body's cells,” Dr. Komaroff wrote. It was easy to make the mRNA. But step two was much harder.

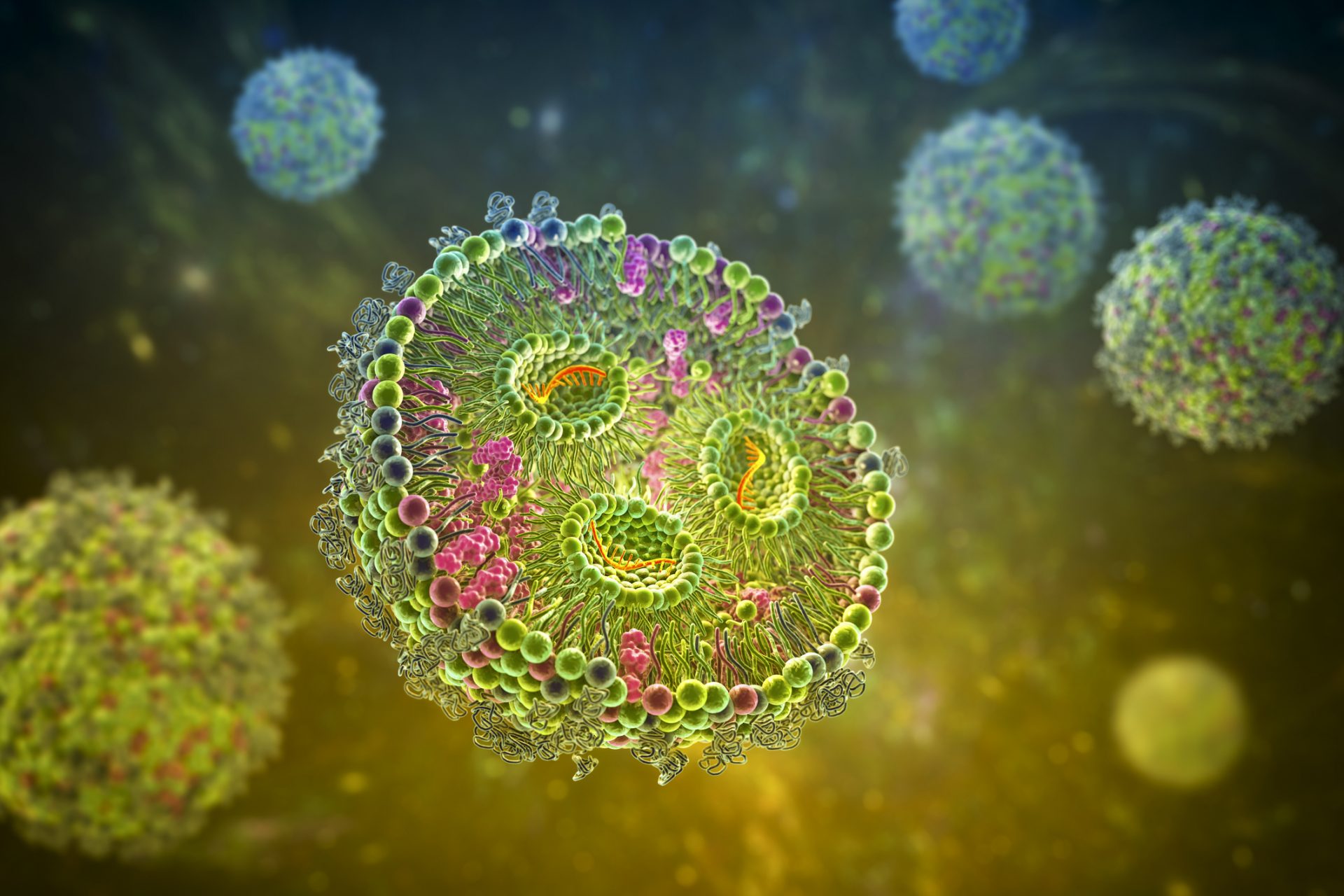

Pfizer explained how mRNA vaccines work in today’s world and revealed that after the mRNA is injected into the body, it is able to enter cells through the use of a “protective bubble” known as a Lipid Nanoparticle.

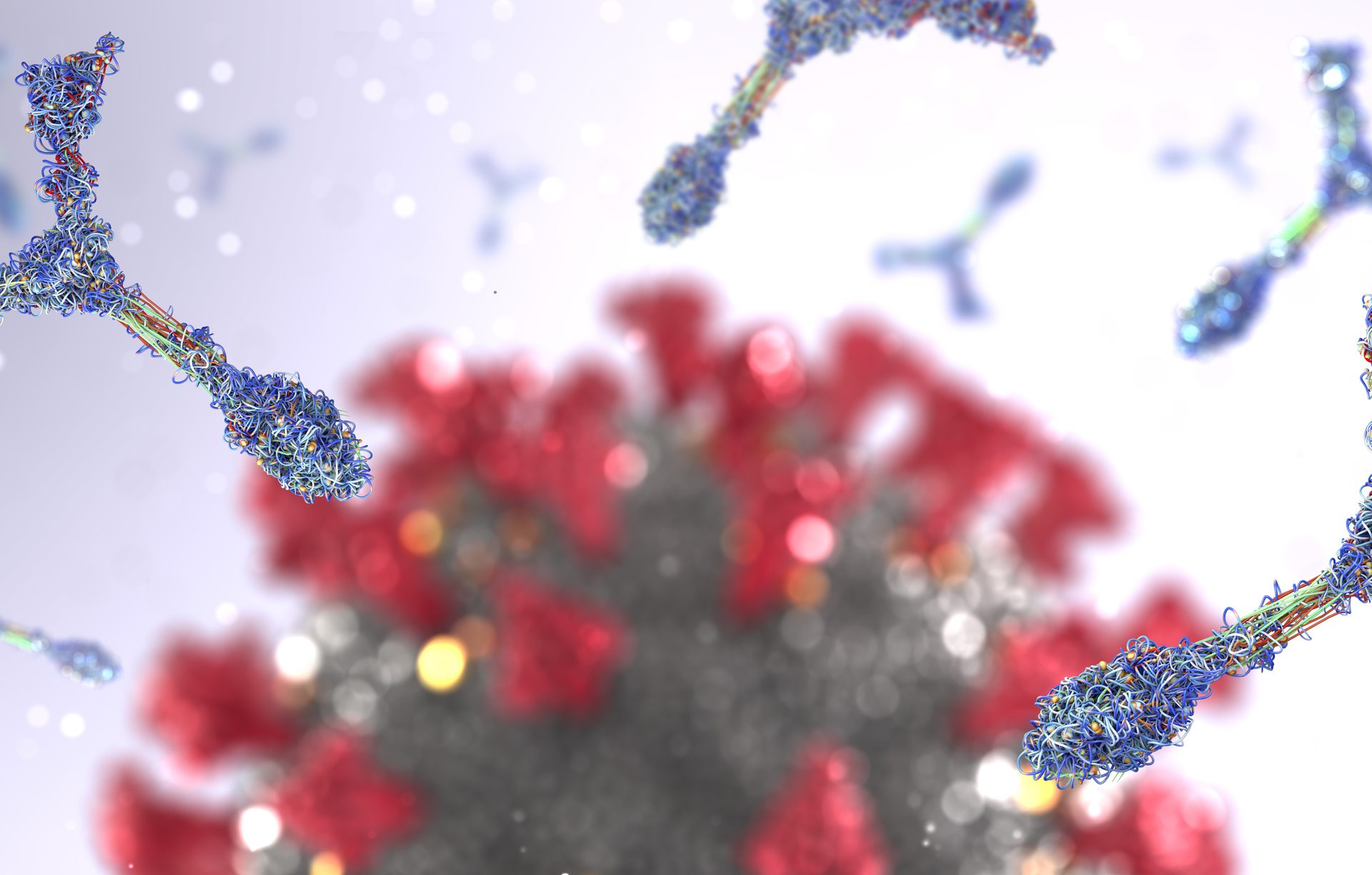

Once the mRNA gets inside the body’s cells, the cell reads the mRNA instructions and it begins “building proteins that match up with parts of the pathogen called antigens.” This is where the real magic begins to happen.

The body’s immune system will see the antigens as foreigners and begin sending out its antibodies (T cells). This trains the immune system to face future threats, and if the real version of the virus comes along your body sounds the alarm.

It took thirty years to figure out how to deliver the mRNA where it needed to go but in one of the world’s most interesting twists of fate. The technology to bring mRNA vaccines to the world was on the cusp of being ready when Covid-19 emerged.

According to Dr. Komaroff, it only took eleven months from the time Covid-19 was found to the development of a vaccine against it. Previously, the faster vaccine developed had taken four years before it was ready for humans.

However, mRNA vaccines weren’t just used to protect the world against pathogens like Covid-19 but rather they can be effectively used to combat a whole host of nasty things that try to attack your body according to Dragony Fu.

Fu is an associate professor of biology at the University of Rochester and he explained to BBC News that you can apply this technology to other foreign invaders such as HIV,” something that was already happening before Covid-19.

"The other category is autoimmune diseases," Fu says. "That is intriguing because it's verging beyond the very strict definition of a vaccine.” Fu also noted that mRNA vaccines could be effective against Zika, herpes, and malarial parasites.

Where the technology will head in the future isn’t known. But it does look like the world is on the cusp of a medical revolution that could render many of the major health problems of today a thing of the past. Would that make us superhuman?

Cancer may be the most promising problem but mRNA vaccines are being tapped to be the next great challenge, and things are progressing quickly. In March 2023, a personal mRNA vaccine against pancreatic cancer showed promise in a small study.

Half of the participants developed a “strong anti-tumor immune response” according to the National Institutes of Health, which added that the new approach developed might “also have potential for treating other deadly cancer types.”

More for you

Top Stories