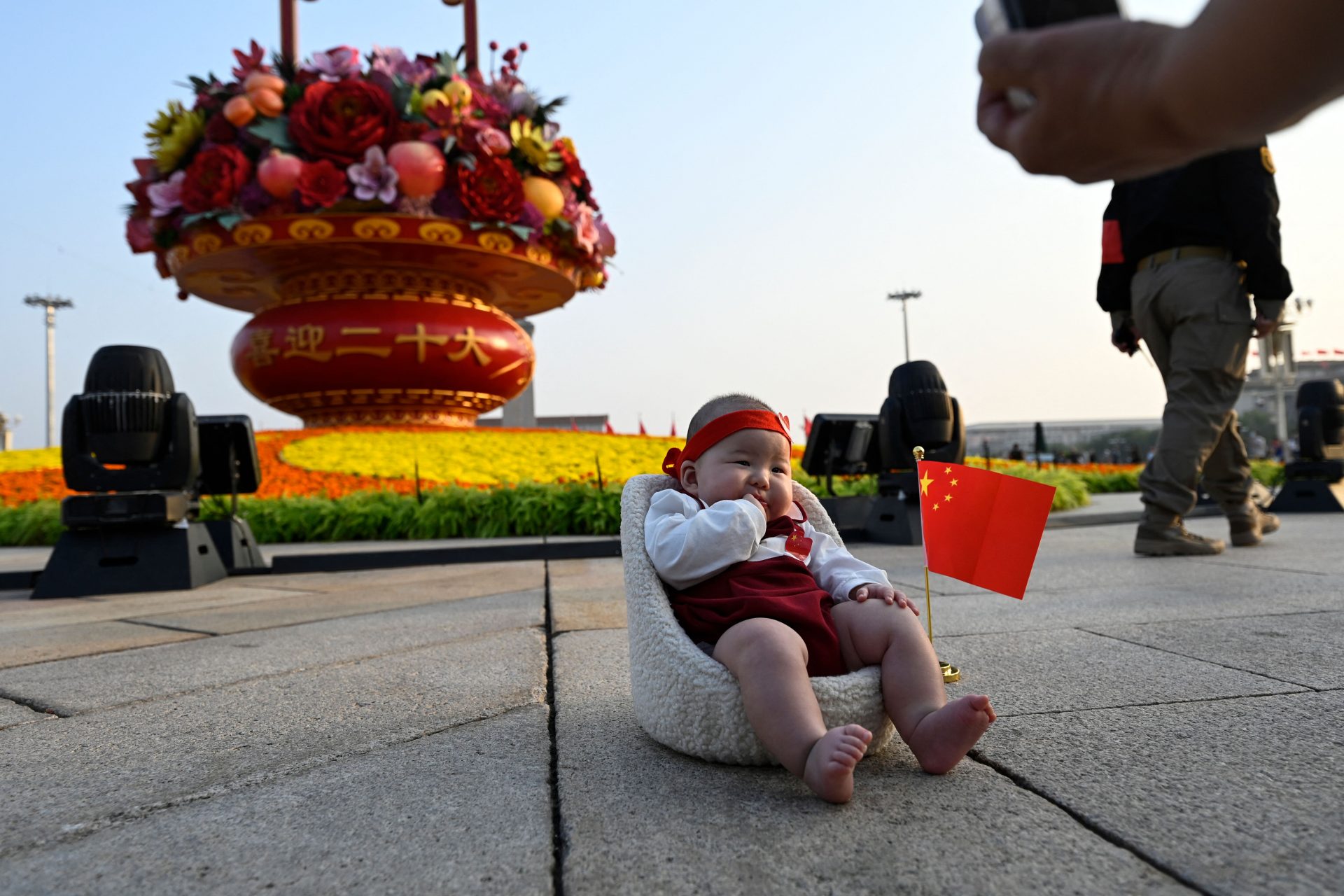

China's population plummets for second year in a row

China experienced a 10% decline in births in 2022, reaching a historic low, despite extensive government initiatives to assist parents.

The decline in births, alarming due to concerns about demographic imbalance, resulted in a mere 9.56 million births in 2022.

For the longest time, China was known as the country with the highest population in the world. However, India became the world’s most populous country in April 2023, according to the United Nations, with a population of 1,425,775,850 at the time.

China's birth rate has been declining for years, but now it has entered what one official described as an "era of negative population growth".

Results from a once-a-decade census announced in 2021 showed China's population growing at its slowest pace in decades.

Deaths also outnumbered births for the first time in 2022 in China. The country logged its highest death rate since 1976: 7.37 deaths per 1,000 people, up from 7.18 the previous year.

This trend is going to continue and perhaps worsen after Covid, according to Yue Su, principal at the Economist Intelligence Unit. Su is among experts who expect China's population to shrink further through 2023.

Su also told the BBC that the high youth unemployment rate and weaknesses in income expectations could delay marriage and childbirth plans further, dragging down the number of newborns.

China's population trends over the years have been largely shaped by the controversial one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979 to slow population growth.

In a culture that historically favours boys over girls, the policy also led to forced abortions and a reportedly skewed gender ratio from the 1980s.

The policy was scrapped in 2016 and in recent years, the Chinese government also offered tax breaks and better maternal healthcare, among other incentives, to reverse, or at least slow, the falling birth rate.

In an attempt to boost birth rates, in May 2021, the Chinese government passed a law allowing women to have up to three children, along with reducing childbirth and education costs.

The Global Times reported that the city of Panzhihua announced in July of 2021 that couples who had more than one child would receive a monetary baby bonus of sorts.

This was the first time an incentive of this kind was offered in China. The Chinese government seems desperate to combat China's demographic decline.

Chinese citizens must find the idea of receiving money for having children odd, given that from 1980-2016, parents were fined if they had more than one child.

Science Magazine spoke to Yong Cai, a demographer at the University of North Carolina, about why young couples choose not to have more children.

Cai told Science that few young couples "put starting a family, or having another child, as their biggest priority."

Many Chinese women say that the changes are too little too late and that they lack gender equality and job security.

In addition, The New York Times reports that many women are angry that the benefits given for having children only apply if they are married, single mothers cannot apply for them.

The statistics from the Chinese government also show that almost 65% of the population now live in urban areas, which is another factor that influences the number of children couples are willing to have.

Demographer Wei Ggo from Nanjing University told Science that the conditions of city living: the high cost of living, expensive schools, and crowded living conditions "reduce people's willingness to have a second child, let alone a third child."

Yong Cai told Science that "despite all the new initiatives and propaganda to promote childbearing," couples simply are against having more children.

China's working-age population (those between 15-64 years of age) of almost one billion has been the key to the country's economic rise.

A massive working age population is how China essentially became "the workshop of the world," as reported by Bloomberg.

However, as the country ages, and if population projections by the United Nations are to be believed, by the 2030s, China's economic situation may look quite different.

Nonetheless, not all demographers agree that China faces a looming demographic crisis. Stuart Gietel-Basten from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology is one of them.

Gietel-Basten told Science Magazine, "... China's population is also getting healthier, better educated and skilled, and more adaptable to technology."

More for you

Top Stories