Cholera epidemic: the causes linked to the resurgence of this disease

Cholera cases are currently exploding around the world, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). For three years, this infectious disease has continued to gain ground, particularly in Africa, where the number of people affected is increasing. How can we explain this resurgence, and how can we deal with it?

The WHO reports that 473,000 cases of cholera were reported to it in 2022, a figure which had already doubled compared to 2021. But the year 2023 recorded an even more marked increase, with 700,000 new cases recorded.

Cholera is an acute bacterial infection of the small intestine, caused by ingestion of water or food contaminated with the bacteria Vibrio cholerae. Typical symptoms of this disease are profuse diarrhea, vomiting and abdominal cramps.

Cholera, and more specifically the severe diarrhea it causes, can lead to rapid and potentially fatal dehydration if not treated in time. It is indeed one of the most devastating infectious diseases, which can cause death in just three days.

@Ante Samarzija / Unsplash

Cholera can spread quickly, mainly when conditions are favorable for transmission. The disease is spread through water and food contaminated by the stool of an infected person. Those infected are usually contagious for 10 days.

@National Cancer Institute Medical / Unsplash

“There is a close link between the transmission of cholera and the absence of clean drinking water and adequate sanitation facilities,” underlines the WHO in a press release published in September 2023.

But then, what is the cause of the current resurgence of this disease? The World Health Organization identifies two main factors: climate change and armed conflict.

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of cyclones, floods and droughts across the planet. A situation that can disrupt access to drinking water. According to the WHO, these extreme climatic phenomena “trigger new epidemics and worsen existing ones.”

@Alexey Demidov / Unsplash

The French daily newspaper Le Monde takes the example of Mozambique, where cases of cholera increased tenfold after the passage of Cyclone Freddy, which deprived part of the population of drinking water at the start of 2023.

Cholera mainly affects poor countries, particularly on the African continent. Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Somalia, Zambia and Zimbabwe are heavily affected by cholera. Note that Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan and Haiti are also hit by the epidemic.

The island of Mayotte, a French department located in the Indian Ocean, near the Comoros, has not escaped the epidemic. According to a report from the Regional Health Agency (ARS) published on May 13, 78 cases have been recorded on the island since mid-March. The ARS also mentions 464 contact cases treated and 4,456 people vaccinated in the overseas department.

Furthermore, Public Health France recalled that most cases were concentrated in Koungou, the second most populous city in Mayotte, "in a precarious neighborhood with difficulties in accessing drinking water and sanitation defects, increasing the risk of spreading the disease."

The French Minister of Health, Frédéric Valletoux (photo) announced that a 3-year-old girl, infected with cholera, had died on the island of Mayotte on Wednesday May 8.

But Frédéric Valletoux assures that the situation in Mayotte is now "under control", as reported by France 24, thanks to "an intervention by health services on vaccination, care, support for those affected", specifies the minister.

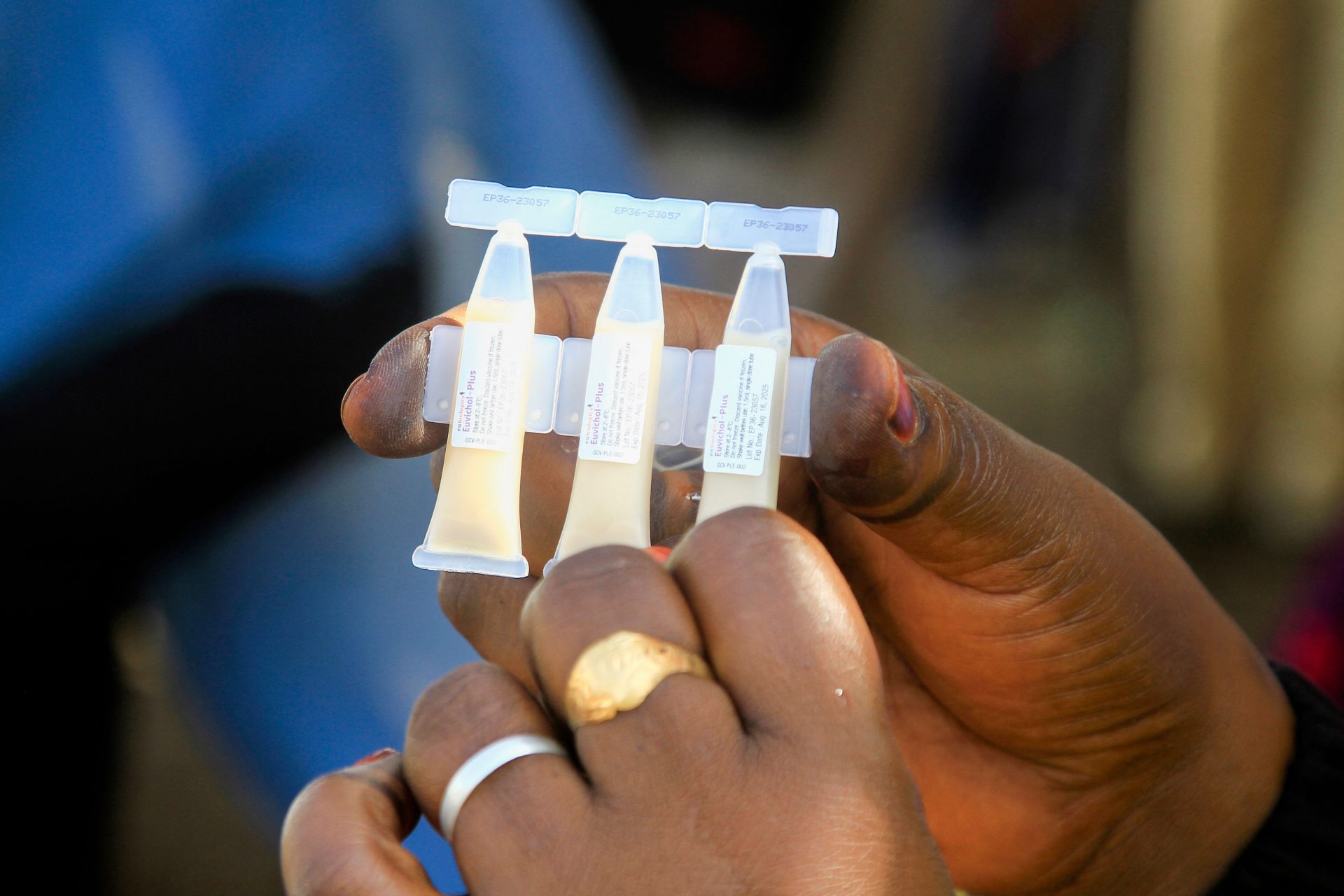

To combat the cholera epidemic, several oral vaccines have been developed and are recommended by the WHO in countries affected by cholera. But faced with the explosion of cases, vaccine stocks are quickly running out. As a result, humanitarian organizations have had to reduce the number of doses administered during vaccination campaigns.

In April 2024, the WHO authorized a new vaccine, Euvichol-S, produced by the South Korean group EuBiologics. “We hope that this new prequalification will enable a rapid increase in production and supply, which many communities facing cholera outbreaks urgently need,” said Dr Rogerio Gaspar, director of the Department of Regulation and WHO prequalification.

More for you

Top Stories