New research finds young blood might be the key to extending life

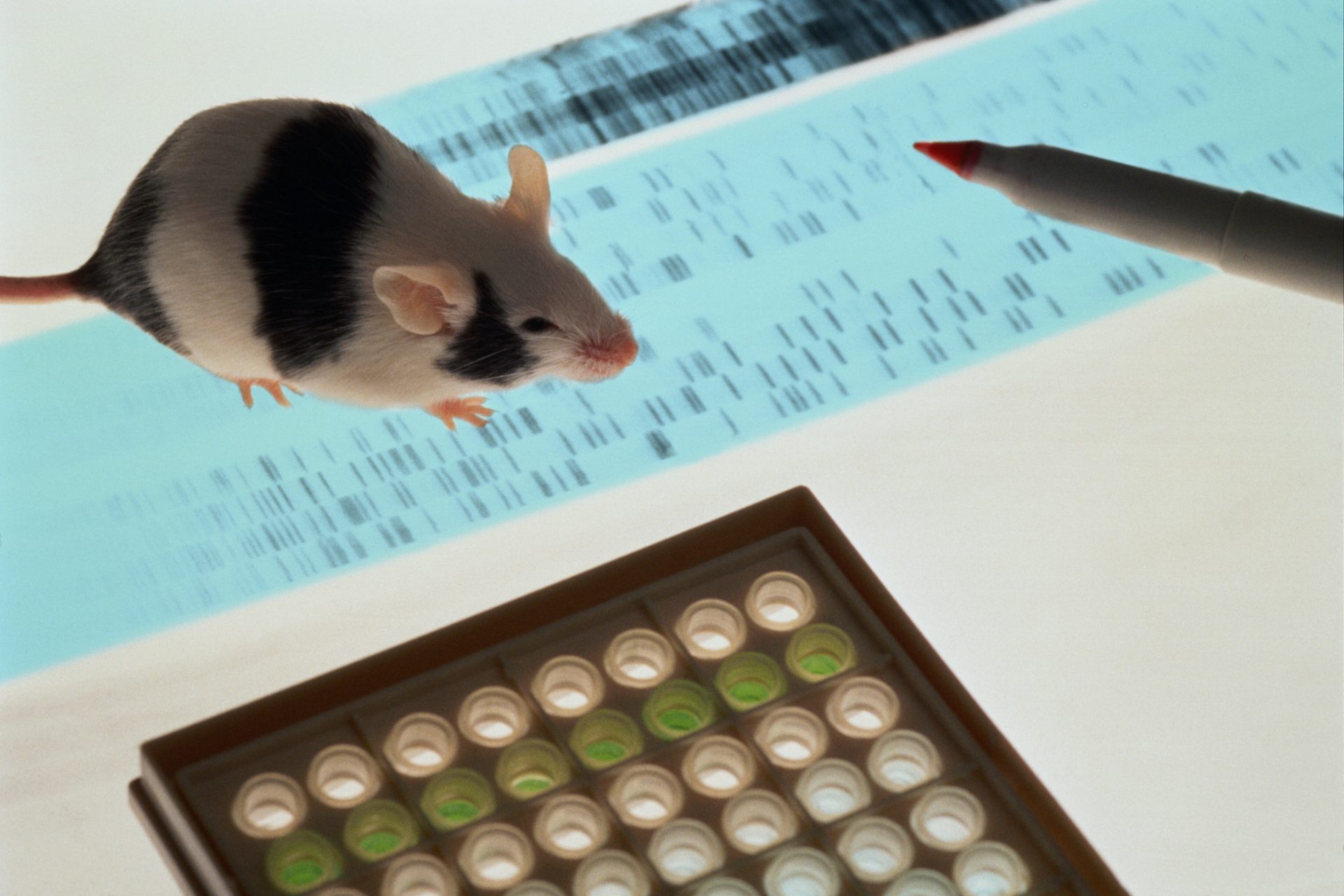

New research from a team of scientists at Duke University just revealed that connecting older mice with the blood of younger hosts extended their lives by a substantial margin.

The scientists surgically attached the blood vessels of older mice to hosts of a much younger age and then later detached the mice in order to see how long the older animals would live.

The infusion of younger mouse blood led the older mice to live between six and nine percent longer, equal to roughly six years for humans according to the New York Times.

The Times also noted that while the experiment didn't necessarily mean humans could benefit from younger blood, it did hint that younger mouse blood had longevity-promoting compounds for the older mice.

“I would guess it’s a useful cocktail,” explained James White, a co-author of the study and biologist at Duke University School of Medicine, to the New York Times when talking about whether or not young blood could revitalize the elderly.

Previous research into intertwining younger and older mice so that their blood flowed in between their bodies, a process called parabiosis, showed that younger blood has rejuvenating effects according to New Scientist.

Parabiosis has been shown to refresh the brain, liver, and muscles of older mice but the technique has never been proven to extend the lives of older mice, at least until now.

That is why Jack White and study co-author Vadim Gladyshev decided to connect older mice with an average age of 20 months to younger mice who were only 3 months old with a goal to examine the effects on longevity.

White explained that they “wanted to know, do the anti-aging effects just go away after you take the mice apart?” And the researchers got their answer when the older mice showed a big improvement in their lifespans.

The research was published in the journal Nature Aging, and White and Gladyshev concluded in their paper that joining the older and younger mice slowed the aging process at a cellular level, which in turn extended their lifespans.

A press release from Duke Health noted the finding was important because it suggested the elderly can benefit from “compounds and chemicals” in younger blood and the discovery could be used as a therapy to speed healing or rejuvenate the bodies of older individuals.

“This is the first evidence that the process, called heterochronic parabiosis, can slow the pace of aging, which is coupled with the extension in lifespan and health,” White said in a press release.

“Our thought was, if we see these anti-aging effects in three weeks of parabiosis, what happens if you bring that out to 12 weeks,” White explained. “That’s about 10% of a mouse’s lifespan of three years.”

Followup examinations of the older mice showed that the benefits they received to their bodily functions persisted for two months, even after they were detached from the younger mice.

Unfortunately, the reasons and mechanisms behind why the blood of younger mice was beneficial for older mice are not yet known, but White is planning to continue his research into the subject.

“Are they proteins or metabolites? Is it new cells that the young mouse is providing, or does the young mouse simply buffer the old, pro-aging blood? This is what we hope to learn next,” White said.

More for you

Top Stories