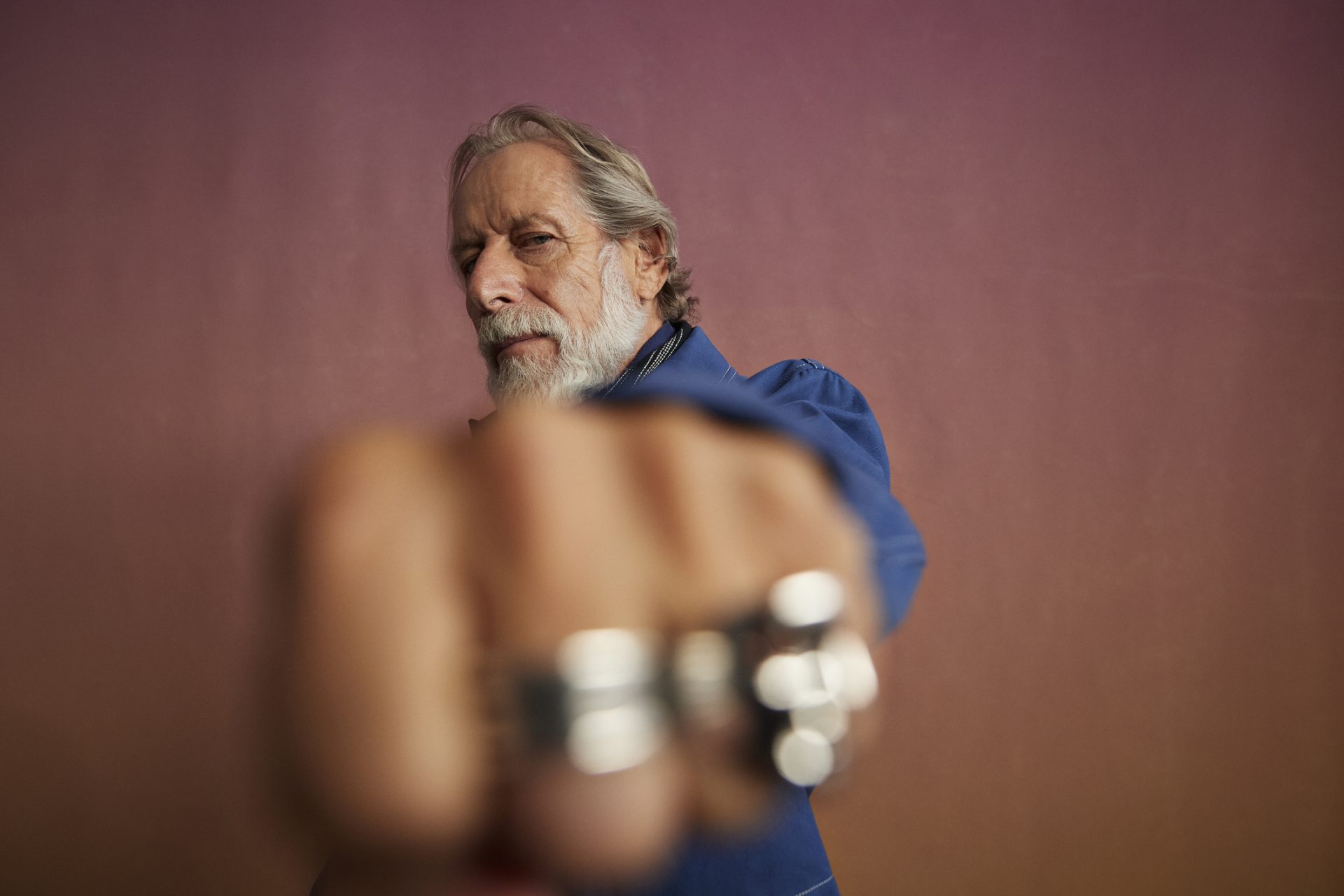

One expert is changing everything we know about aggression and self-control

A new study has revealed that aggression may not be the result of a lack of self-control but rather a product of one’s self-control designed to inflict a more significant retribution.

Violence is not okay and most people would agree that attacking another person either mentally or physically is the result of a loss of self-control rather than it being exercised.

However, the notion of a loss of self-control in aggressive behavior has been challenged by a researcher from Virginia Commonwealth University who says we’ve got it all wrong.

“Typically, people explain violence as the product of poor self-control,” explained Ph.D. and associate professor of social psychology David Chester said in a press release.

“In the heat of the moment, we often fail to inhibit our worst, most aggressive impulses. But that is only one side of the story.” Professor Chester continued.

Chester’s meta-analysis work revealed that aggressive people aren’t losing self-control when they lash out but rather are using their self-control to inflict more pain on others.

For example, Chester noted that vengeful people exhibit more predetermination in their self-control and behavior, allowing them to delay the gratification gained from revenge.

Vengeful people who believe they’ve been wronged may take their time in exacting their revenge in order to exact the most retribution on those who they believe wronged them.

“Even psychopathic people, who comprise the majority of people who commit violent offenses, often exhibit robust development of inhibitory self-control over their teenage years,” Chester said.

Chester also found that aggressive behavior could be linked to increased activity in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain the social psychology professors noted was involved in self-control.

All of these findings led Chester to suggest that aggression was more likely a product of a person's self-control rather than a result of one losing their ability to control themself.

“This paper pushes back against a decades-long dominant narrative in aggression research, which is that violence starts when self-control stops,” Chester explained.

“Instead, it argues for a more balanced, nuanced view in which self-control can both constrain and facilitate aggression, depending on the person and the situation,” Chester added.

It might not seem like this potential discovery matters in the grand scheme of things but understanding how some people express their aggressive tendencies can help us guide how we treat society’s most worrisome people.

For example, Chester suggested that we should be cautious when treating some people since approaches teaching them to better control their aggression may not be the right solution when seeking to reduce violence.

“Indeed, we may be teaching some people how best to implement their aggressive tendencies.” Chester said before adding that future research should be “guided by this new paradigm shift in thinking.”

More for you

Top Stories