Exploring Putin's rising connections in European power circles

Following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia, under the leadership of President Vladimir Putin, has become a pariah state in the eyes of the Western world.

However, it seems that a crack has formed in the bloc of nations opposing Russia’s “special military operations”.

Slovaks voted in, and pro-Russian Robert Fico become Slovakia’s next Prime Minister on October 25, 2023.

The New York Times describes Smer, Fico’s party, as nominally leftist, populist and Russia-friendly, blaming the war on the Kyiv government and the pressure of the West.

Smer obtained about a quarter of the votes, forming government with the socially-conservative pro-European Hlas (itself a division from Fico's party) and the right-wing ultranationalist pro-Russian Slovak National Party.

Image: @pino_rumbero / Unsplash

Meanwhile, the liberal Progressive Slovakia got second place in the elections and now leads the opposition in parliament.

Al Jazeera comments that Slovakia so far has helped supply military equipment to Ukraine and accepted refugees from the war, but that could change under Fico.

Fico, who already was Prime Minister between 2006 and 2010 and again between 2012 and 2018, has promised to cut funding going towards Ukraine and begin peace talks between Moscow and Kyiv.

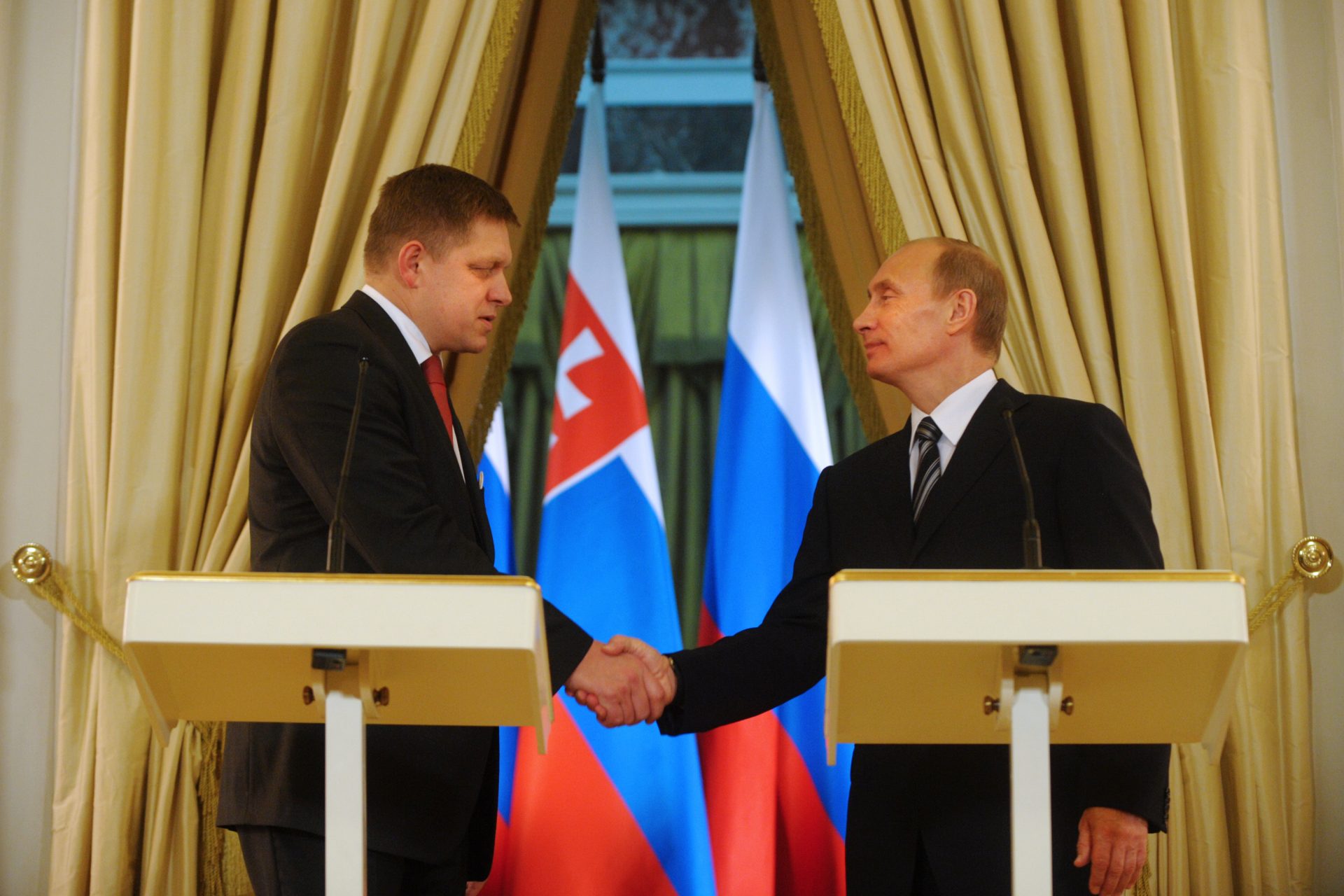

Pictured: Fico and Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2009

Al Jazeera points out that Fico was forced to step down in 2018 after the murder of Ján Kuciak, an investigating journalist looking into the connections between the Italian mafia and Fico’s inner circle.

German news agency DW comments that Fico’s victory could be a problem for the European Union and NATO, since Slovakia is a member of both.

French newspaper Le Monde highlights that this could complicate even further a common European policy towards Russia, which is already difficult due to the opposition of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

According to Le Monde, Fico promised during the campaign not to reject military aid to Ukraine, arguing that it was stalling the conflict, but also oppose sanctions towards Russia and set to normalize relations towards Moscow.

Fico also promised to work in tandem with the Hungarian government, which could break Orbán’s isolation in his anti-Kyiv position within the EU.

According to The New York Times, Fico’s campaign was defined by conservatism, nationalism, anti-LGBT rhetoric and promises of generous welfare handouts packaged in an anti-liberal agenda that was effective in small towns and rural areas.

Group research analyst Dominika Hajdu was quoted by The New York Times arguing that the war in Ukraine was seen as a secondary issue during the election. Things like food and fuel prices and a social divide between conservatism and progressivism were more influential to the average Slovak voter.

Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba was quoted by Al Jazeera affirming that Fico’s partners in government will be decisive in defining Slovakia’s relation with Russia and the rest of the European Union.

More for you

Top Stories