Why Russians have been snitching on their anti-war neighbors

Since Russia invaded Ukraine more than two years ago, critics of the war were repressed by authorities and the Kremlin started to introduce more censorship laws.

According to the Russian human rights monitor OVD-Info, there are at least 813 criminal cases against anti-war dissidents under Russia’s wartime censorship laws.

In March 2022, Putin said in a public speech that the "self-cleansing of society" would only strengthen the country, adding that Russians “will always be able to distinguish true patriots from scum and traitors and will simply spit them out like an insect in the mouth.”

Following Putin’s comments, ‘A Just Russia’ party created a website where Russians can send in information about “unpatriotic” citizens, The Moscow Times reported.

Photo: Christin Hume/Unsplash

Many similar campaigns followed in different cities created to snitch on “politically incorrect neighbors, colleagues and even family members", according to the Russian outlet.

Moscow student Elmira Khalitova was denounced by her own father, who claimed, when drunk, that she had been calling on people to “murder Russians.” She denies having said “anything like that”.

Khalitova, 21, told The Moscow Times that her father was driven to this dramatic step by a “TV propaganda frenzy,” as his political views are heavily influenced by tightly controlled state television channels and political shows.

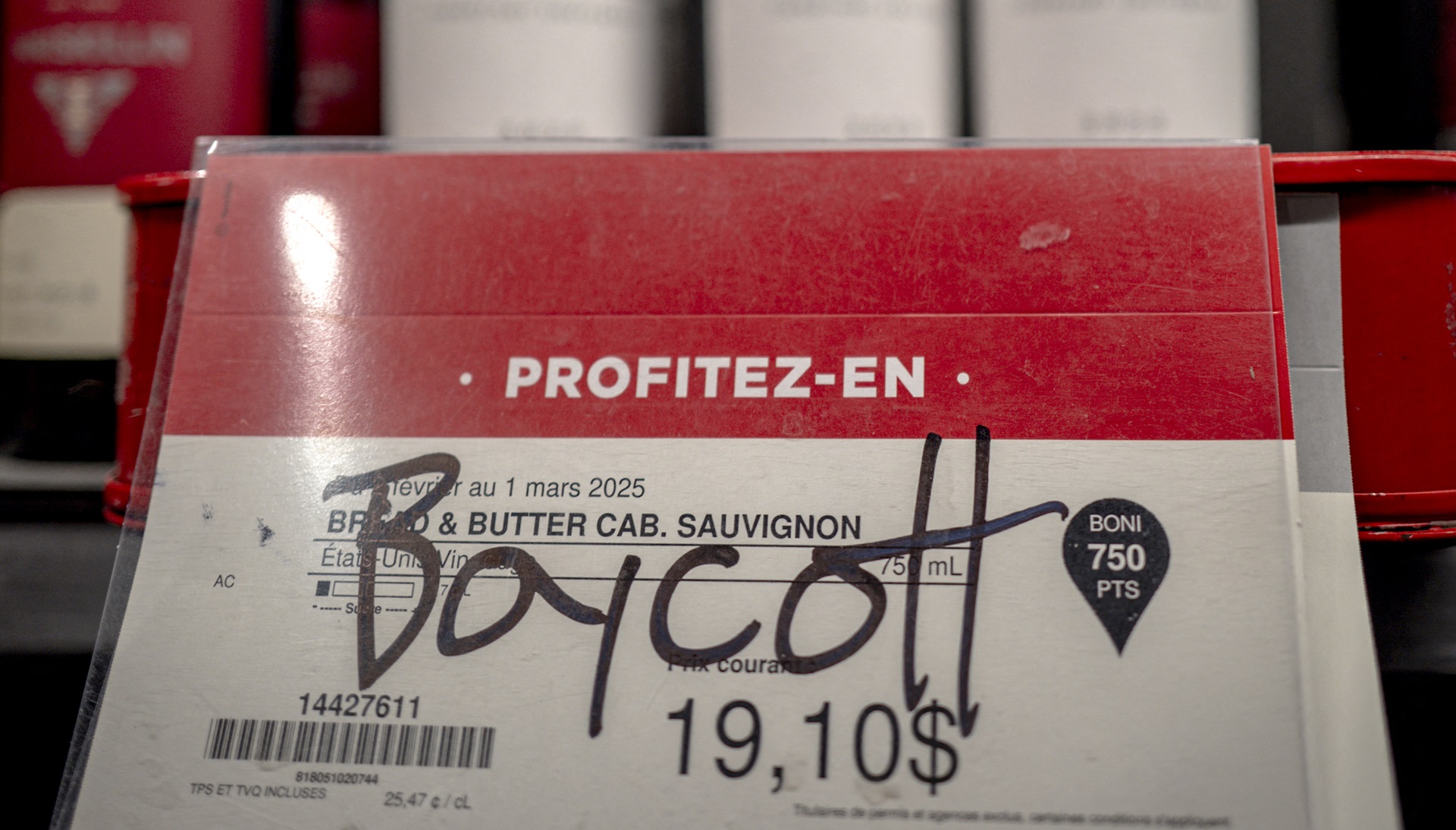

Following Russia’s bombing of a theatre in the Ukrainian city of Mariupol in March 2022, St. Petersburg-based artist Alexandra Skochilenko swapped supermarket price tags with stickers containing information about the attack that killed hundreds of civilians.

A fellow store customer reported her act of resistance to the police and she was arrested for “spreading false information”. Now, she’s facing up to 10 years in prison, according to an Al Jazeera report.

Photo: Rey Joson/Unsplash

“The [Communist] Party has a large army of voluntary informers at its disposal. We have a complete picture about each and every person,” claimed the USSR leader Konstantin Chernenko (pictured).

In resorting to denunciations, many Soviet people sincerely wanted to help the state in the fight against the “enemies of the Revolution”. Others used the system exclusively in their own self-serving interests, according to historian Boris Egorov.

Self-proclaimed snitch Anna Korobkova told the BBC that she learnt the practice from her grandfather, who was an anonymous informant for the Soviet secret police during Stalin's reign.

Anna claims to have written 1,397 denunciations about anyone who criticises the war and says people have been fined, fired and labelled as foreign agents as a result of her condemnations.

"I do not feel sorry for them. I feel joy if they are punished because of my denunciations," she told the BBC.

Russian officials told the BBC they are inundated with denunciations since the war began, spending large amounts of time investigating and revising "endless charges".

Photo: Quino Al/Unsplash

Denunciations are also common within government agencies. Yelena Kotenochkina, a deputy in Moscow’s Krasnoselsky District Council, had to flee Russia after calling it a “fascist state” during a council meeting, several media reported.

More for you

Top Stories