Stonewall riot: history of an LGTBIQ+ symbol

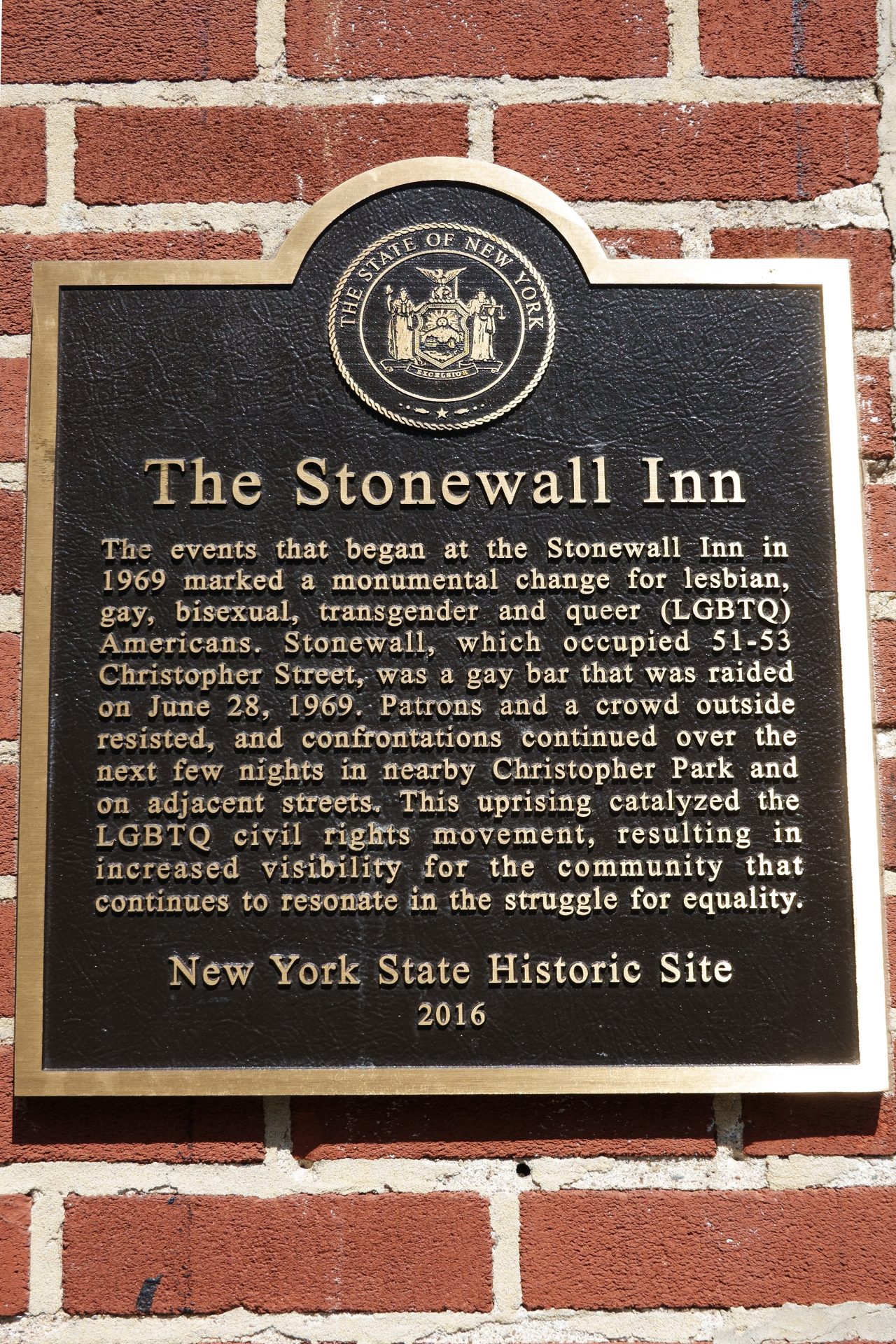

In June 1969, 55 years ago, members of the LGTBIQ+ community were enjoying their night at the Stonewall Inn, a New York bar run by the mafia, when the police began a raid. These interventions were not new to the community, but this time people fought back. Thus began the Stonewall Rebellion, a symbol of modern LGTBI+ movement, which lasted for five consecutive nights.

At one in the morning, the bar was packed with people when six police officers began the raid. Approximately 200 clients, including lesbians, gay men, transgender people, runaway teenagers and drag queens, were thrown onto the streets. When the crowd turned against the police, the officers sought refuge inside the bar.

As Robert Bryan tells the BBC, at first, the atmosphere on the street was festive. He was 23 years old at the time: "There was laughter and jokes. People came out of the bar making poses and bowing." Everything changed when a drag queen was attacked by one of the agents.

From there people started throwing coins at the police and everything got worse when a lesbian struggled against officers who were trying to put her in a car. So the coins became stones and bottles.

A chalk message on the walls of Christopher Street called for the rally: "Tomorrow night Stonewall." The distribution of leaflets the next day also invited people to the bar. The demonstrations at Stonewall were not the first, but in the following days they got more intense and violent, and became the origin of a stronger and more organized resistance of the LGTBIQ+ movement.

In the 1960s, homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder (it only ceased to be so in 1973). Most states in the United States had laws prohibiting same-sex relationships and arrested people for "crimes against nature," prostitution, or lewd behavior.

According to historian Barry Adam, between 1947 and 1950 in the United States, 1,700 federal job applications were rejected, 4,380 people were expelled from the military, and 420 were fired from their government jobs because they were suspected of being homosexual.

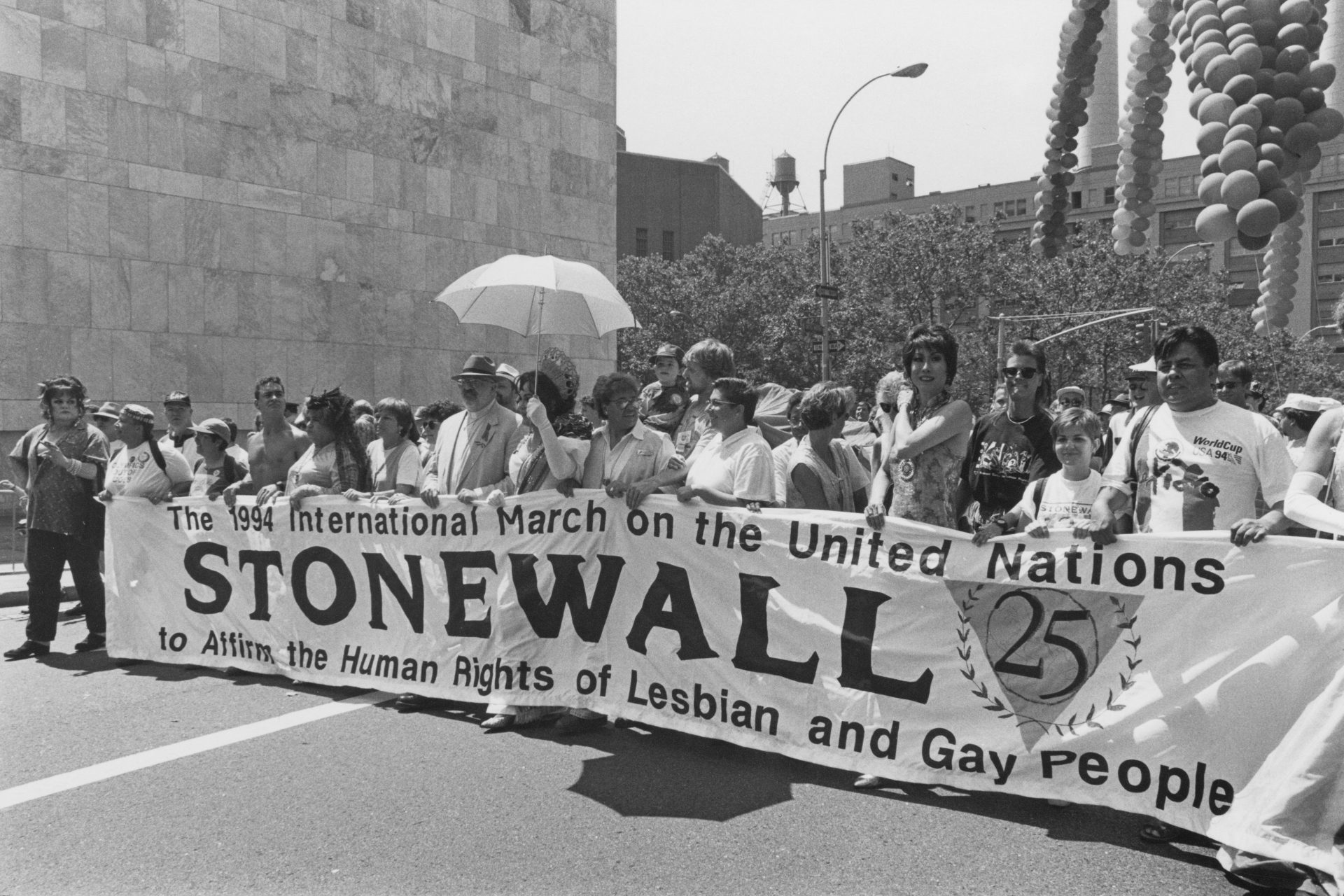

Although there were already organizations fighting for LGTBIQ+ rights, things took on a larger proportion after the rebellion. A year later, what is now considered the first gay pride march was held in New York: activists led by Craig Rodwell commemorated the anniversary of Stonewall with what they called Christopher Street Liberation Day .

"Everyone in the crowd felt like we were never going to go back," Michael Fader recalls to National Geographic. Fader had been present at the raid; "The bottom line was that we weren't going to leave. And we didn't."

Thanks to Stonewall and many activists who came before and after, Pride Month and LGTBIQ+ marches today occur in different countries around the globe. Although they celebrate the achievements achieved by the group, the parades are also demonstrations of the fight for rights and dignity, and resistance of a group that is often still marginalized in society.

More for you

Top Stories