The impact of biases on Nobel Prize outcomes

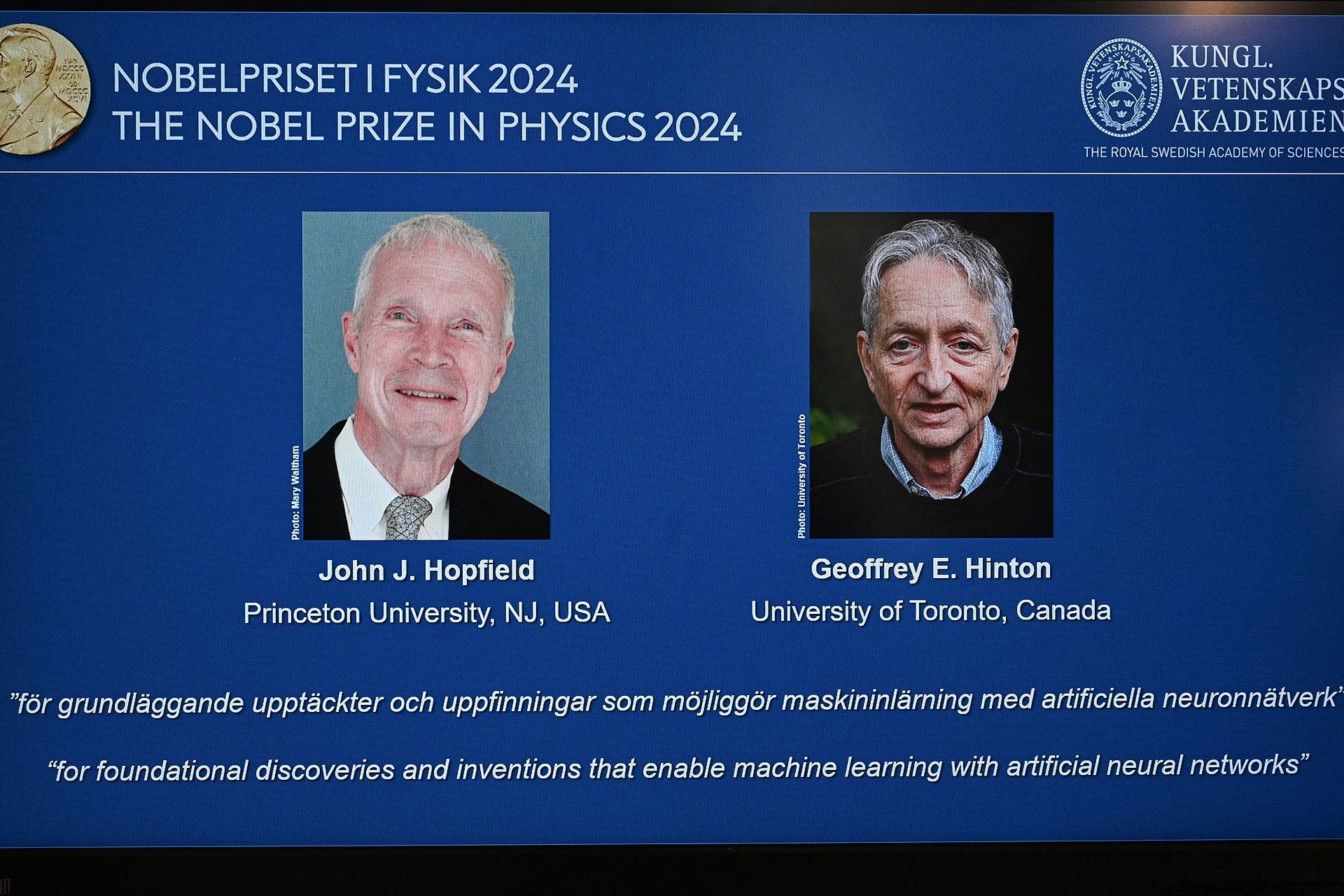

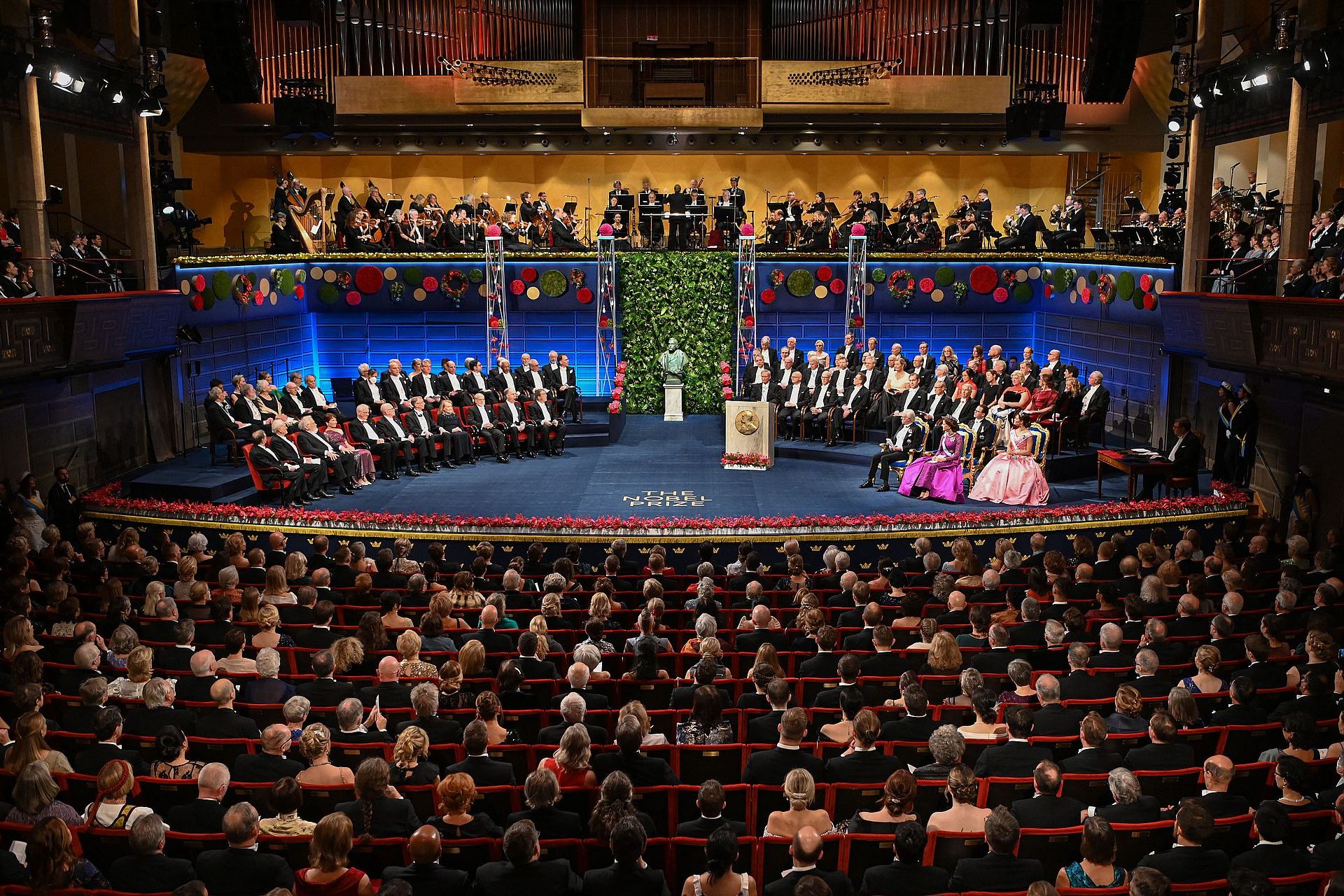

From South Korean writer Han Kang in literature to American and British-Canadian scientists John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton in physics, among others, the Nobel Prize has once again honoured eminent figures in the arts and sciences.

Every year, many people from different disciplines are nominated, but just a small number manage to win the prestigious prize and all the fame that comes with it.

But how are the winners selected? And are the awarding procedures completely impartial? According to an investigation by Nature magazine, things are not so simple.

To carry out their analysis, the journalists used data covering the 646 recipients of the 346 Nobel Prizes in science (physics, chemistry and medicine) since the creation of the award. As a reminder, there is no Nobel Prize in mathematics.

Photo: Artturi Jalli / Unsplash

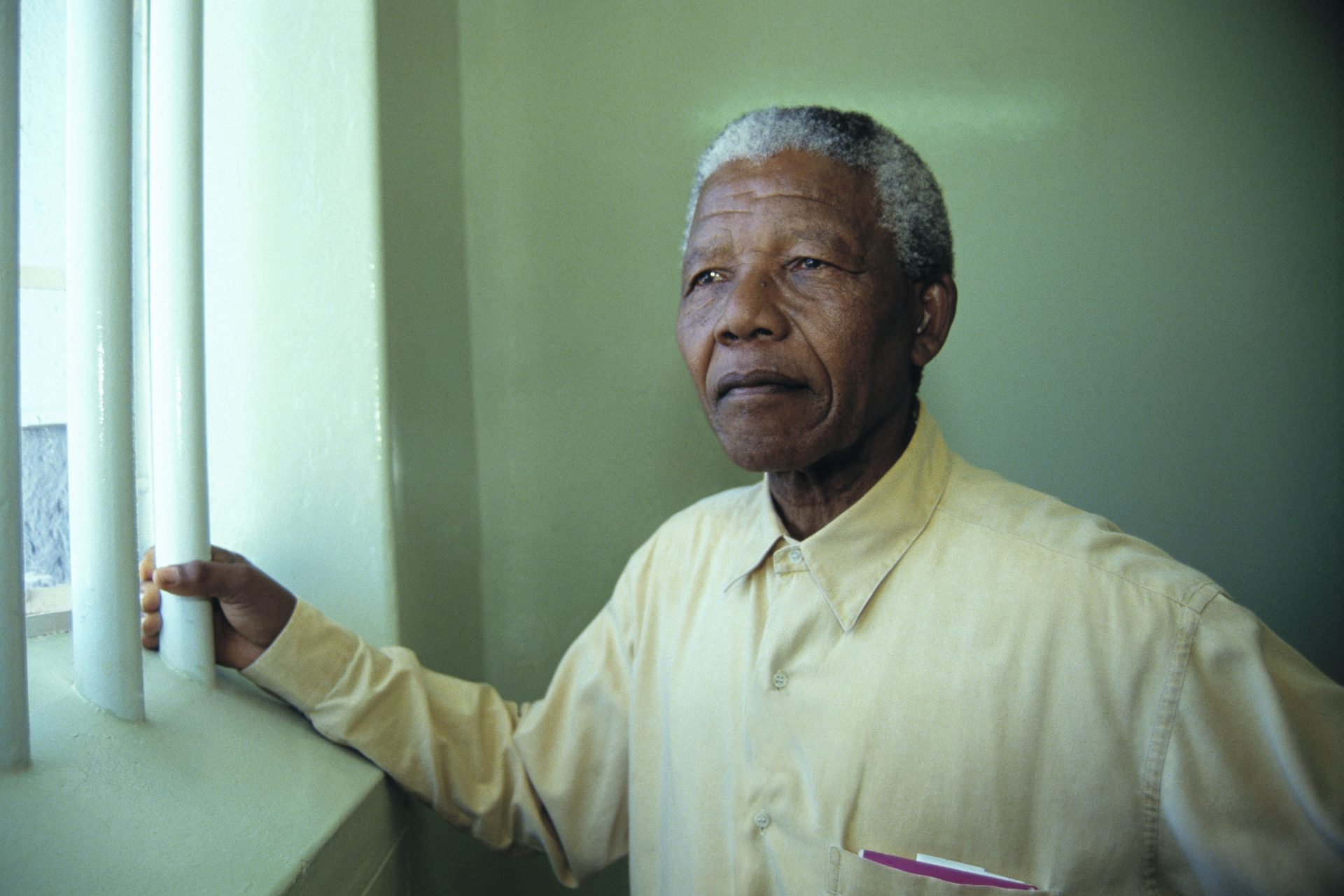

Only 17 Black people have won Nobel Prizes in the categories of literature, peace and economics. However, when it comes to the Science categories, no Black person has ever been awarded.

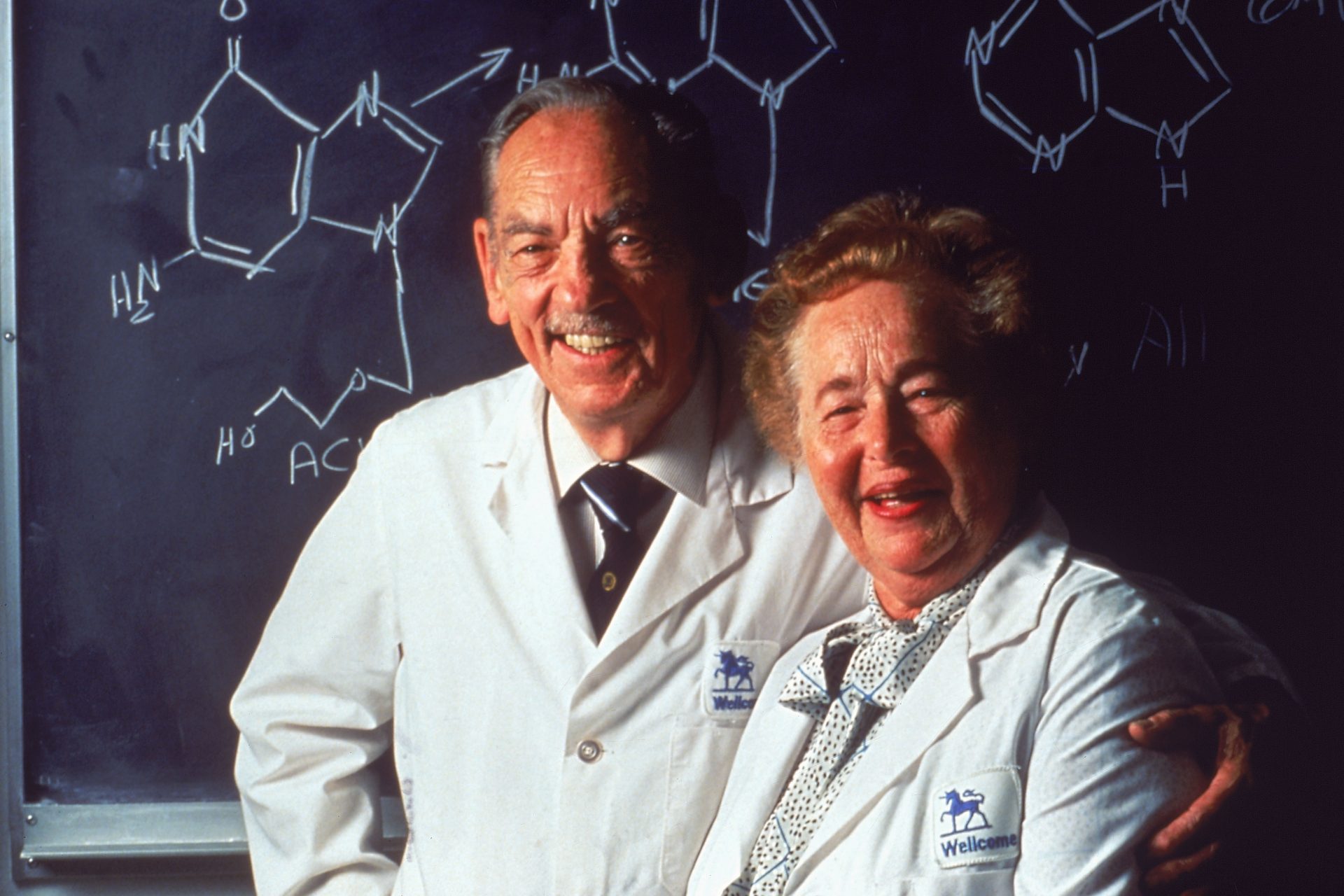

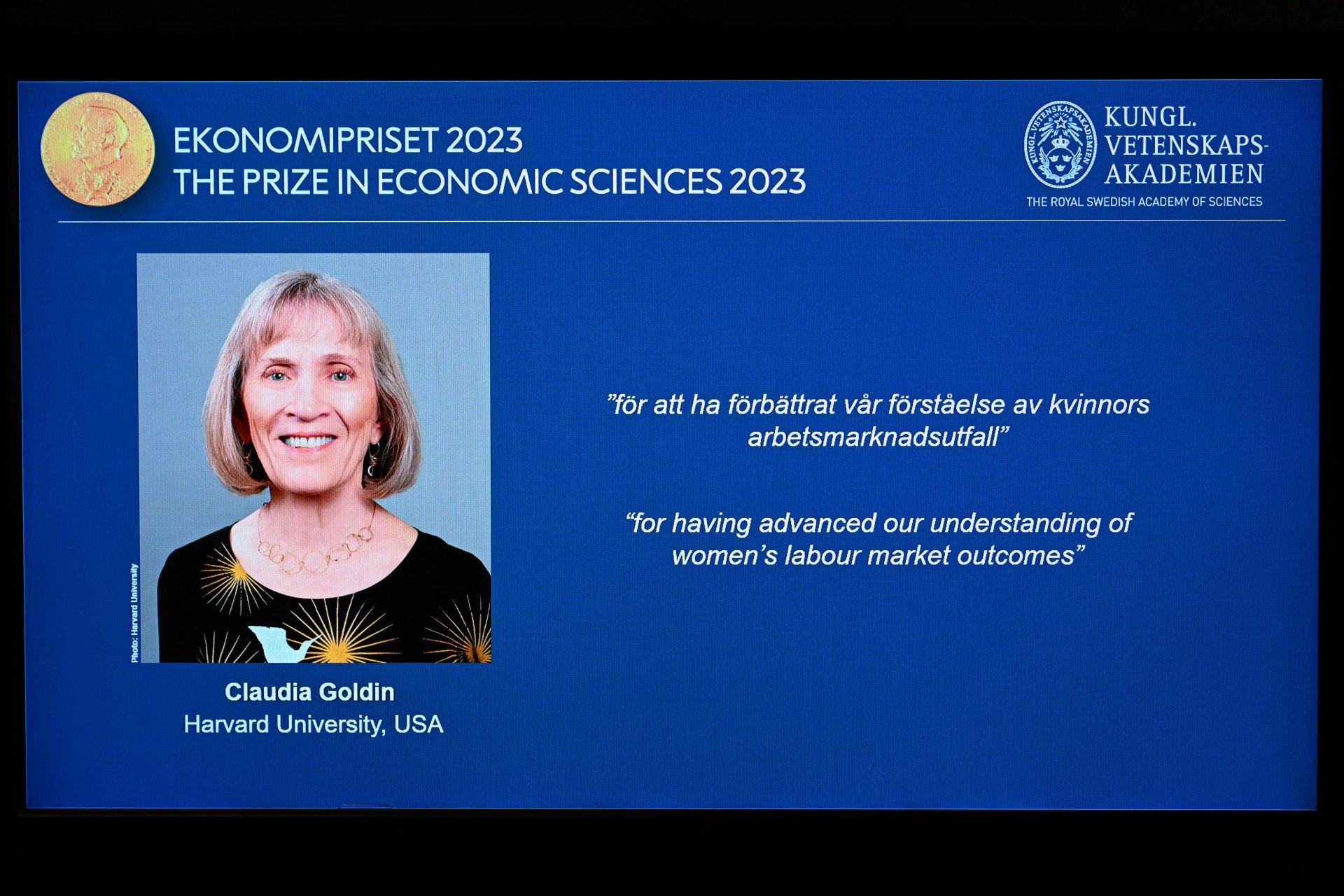

Unsurprisingly, men have historically been heavily favored in the awarding of prizes. During the entire 20th century, only 11 Nobel Prizes were awarded to women in these three disciplines.

The situation of women scientists has improved slightly in recent times, with 15 women having received awards since 2000, more in a quarter of a century than in the entire previous century.

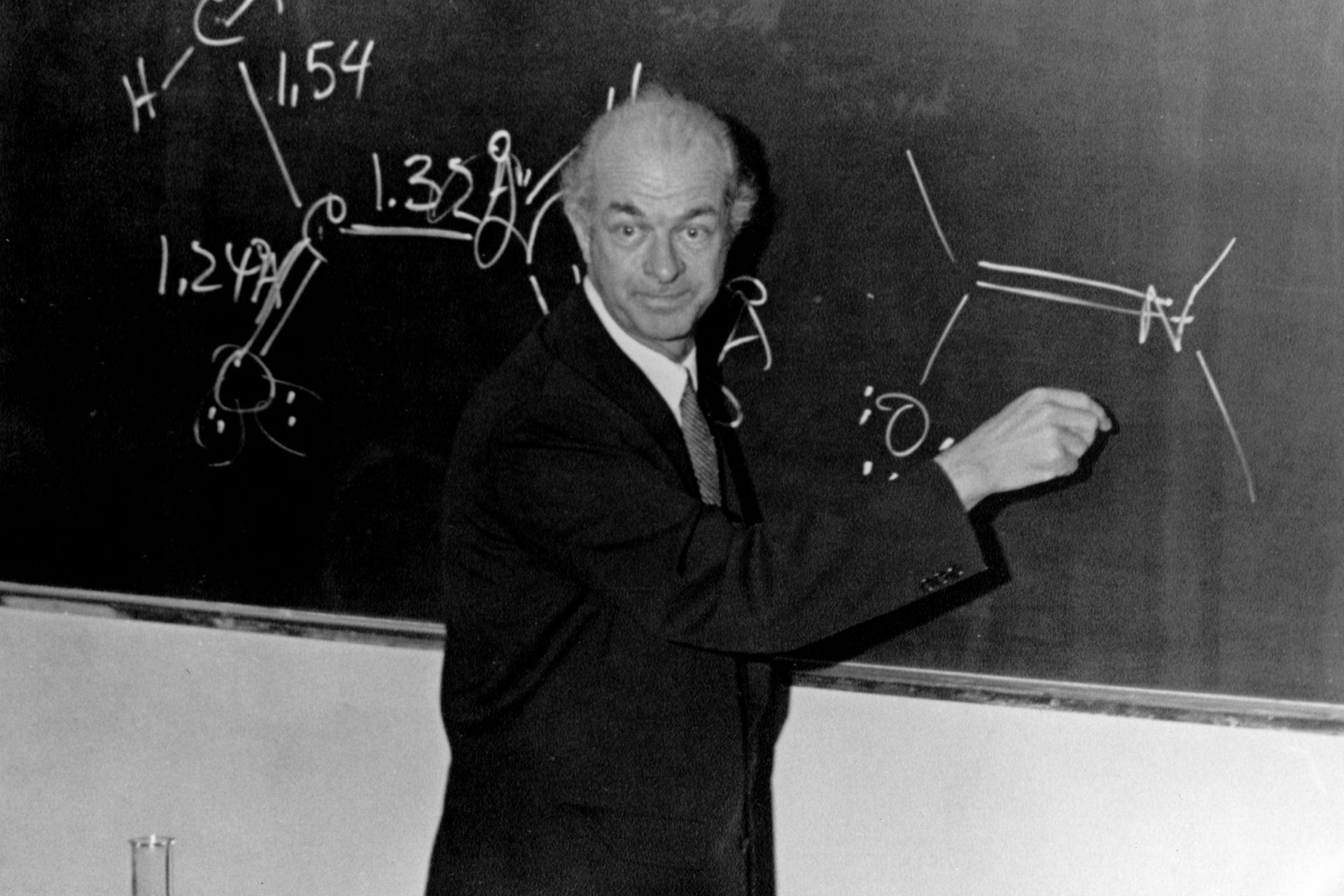

The article recommends starting a "Nobel-worthy" project early, because the average time between presenting a remarkable scientific work and receiving a prize has increased from 14 years before the 1960s to 29 years in the 2010s.

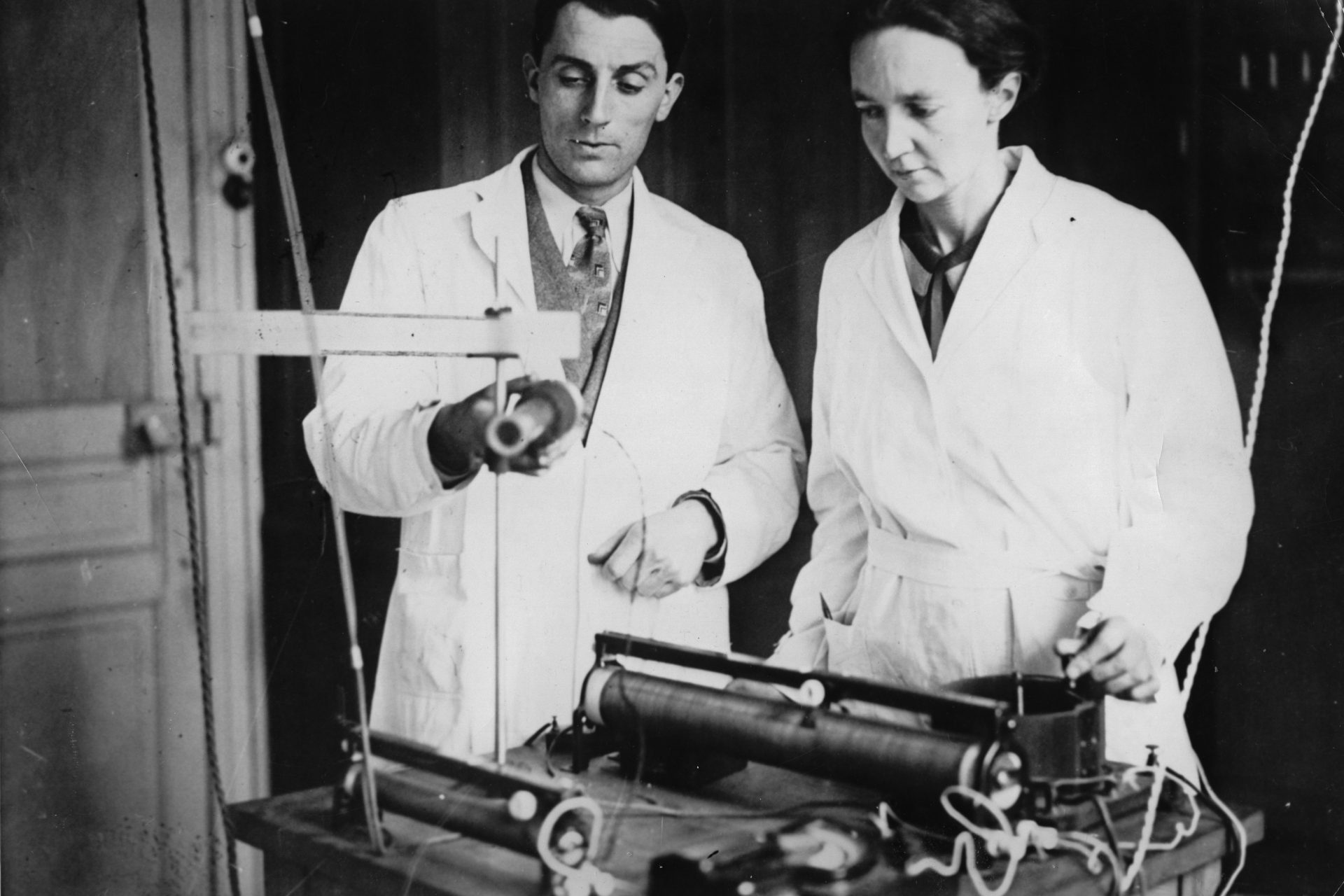

"You can greatly increase your chances of winning a Nobel Prize by working in the lab of a scientist who has won it or will win it in the future, or by working with someone whose mentors have won it," the article adds.

"One might expect that many distinct groups would emerge as separate academic families. But it turns out that almost all Nobel laureates share some connection, however distant, as this sprawling network shows," the authors continue, with an infographic to support their work.

Photo: Alina Grubnyak / Unsplash

The article notes that 702 of the 736 Nobel Prize-winning scientists as of 2023 are or were part of the "same academic family," being linked by an academic connection at some point in their careers.

Photo: Ivan Diaz / Unsplash

There are several hypotheses that can explain this state of affairs, the simplest being that talent naturally attracts talent, in science as in other fields.

A more critical explanation would be that previous laureates tend to promote their successors, with Nobel committees playing a key role in these nominations.

The analysis also reveals the over-representation of certain research fields, such as particle physics, cell biology, nuclear physics and neuroscience, each of which accounted for at least 10% of the Nobel Prizes in science between 1995 and 2017.

More unusually, the authors noted that first names beginning with the letters "A" and "J" are over-represented among the winners, with 62 and 69 winners each respectively.

Photo: Algebra Digital / Unsplash

Asked by Nature about bias in the selection of recipients, the Nobel Academy said it was "continuously working to improve the nomination process."

Indeed, the committee aims to "expand nominations in terms of gender, nationality and subjects in the fields of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine," they said.

Never miss a story! Click here to follow The Daily Digest.

More for you

Top Stories