China's ownership of rare metals could become a major problem

China is one of the biggest (if not the biggest) economies in the world. As such, it can build up or undo entire markets. However, now Beijing has just one aim at its sight.

Rare-earth elements are 17 metals, such as neodymium or dysprosium, used for technology and industry, and in countless devices from mobile phones and computers to batteries and car engines.

Rare earth elements have also been called “green gold” because of their importance in the environmentally friendly energy industry. These materials have great potential as electric conductors, plus enormous magnetic properties.

Paradoxically, since they are considered a necessary resource for green energy and an alternative to climate change, they have also become an environmental problem.

The name “rare earth” is not related to its rarity, but rather to how difficult it is to locate and extract. These minerals are mixed with other elements, so they are not usually found in large quantities nor in pure form.

The extraction process for rare earths there is more difficult and more expensive. Plus, these metals must be separated from other elements through acids, which can generate toxic and radioactive waste.

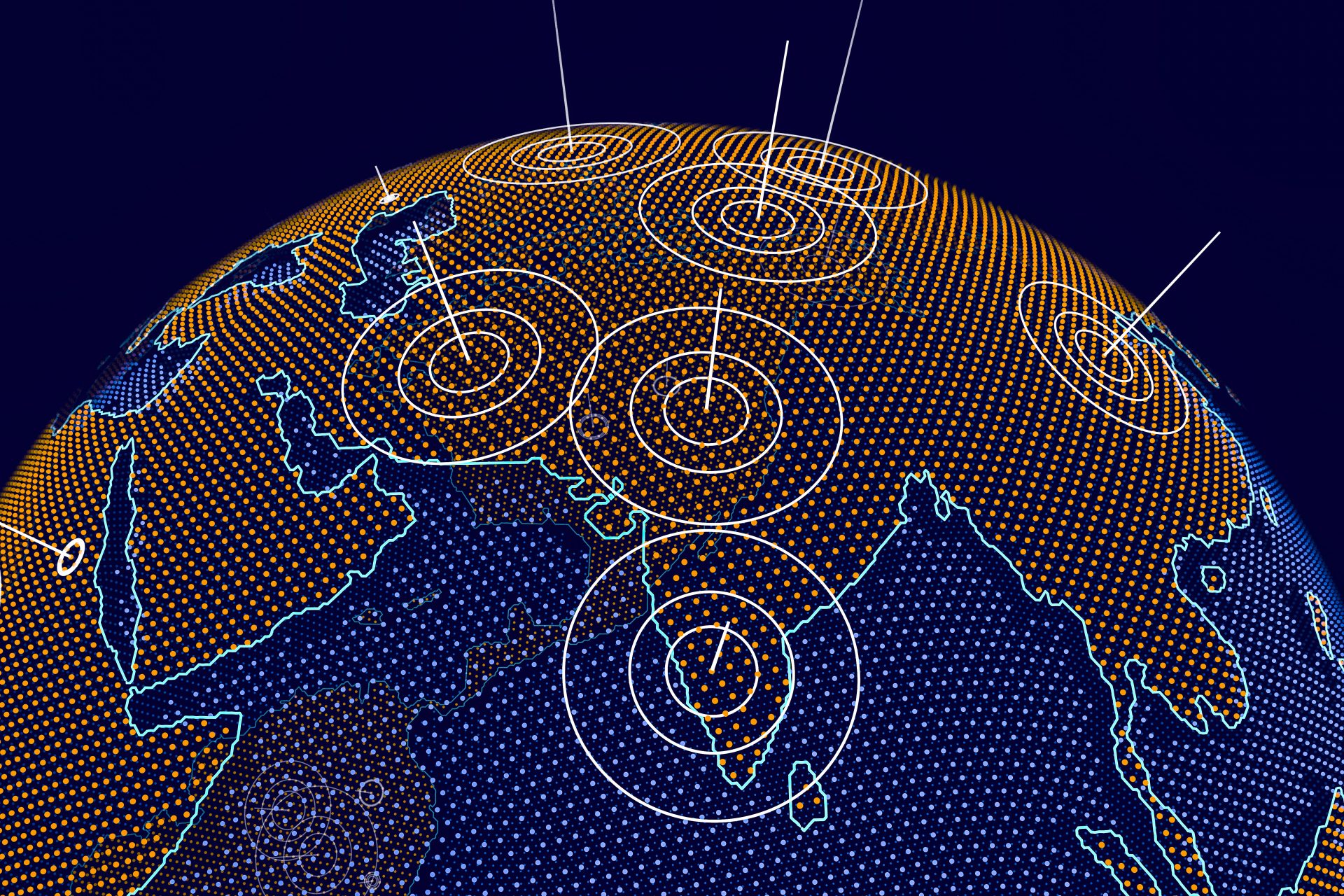

China is the main producer of rare-earth elements. According to 2022 data from Statista, the Asian superpower is leading the rare metals market, with 210,000 metric tons.

The United States is the second-biggest country producing rare-earth metals by volume, although by a long shot: 43,000 metric tons, per Statista. Almost four times less than China!

In fact, China's output represents approximately 70% of the world's production of rare metals. At the same time, the demand for the production of rare earth elements has increased by 25% in just one year.

China is also home to the largest reserves of rare-earth materials, close to 44 million metric tons, compared to 130 million metric tons worldwide, according to Statista.

Vietnam, Brazil, and Russia are among the countries that possess the highest concentration of rare-earth minerals, with reserves somewhere between 21 and 22 million.

China's interest in rare earths is not new. As early as 1987, then-Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping stated “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”, according to the Financial Times.

China's dominance in the production and ownership of rare-earth minerals gives Beijing leverage in key markets, such as technology, pressuring the United States in more than one way.

Europe is also affected. The region depends almost entirely on China for supplying and processing rare metals. According to the Financial Times, Europe imported around 98% of rare-earth elements from China, which many see as a serious economic threat.

Rare earths are used, for example, in the automotive industry and especially in the engine of electric vehicles. China already provides fierce competition, with much lower prices. A supply-chain disruption would deeply harm automakers in the West.

Meanwhile, demand for rare earths continues to be on the rise. The Financial Times writes that the demand is expected to multiply by five circa 2030.

Faced with dependence on China, Europe tries to diversify rare metals suppliers to reduce Beijing's power.

Promoting the rare metals industry in the United States is an option. For instance, there's Mountain Pass, a mine and processing plant for rare-earth materials owned by MP Materials, and located in California.

As the Financial Times explains, between 1965 and 1995, Mountain Pass supplied most of the world's rare earth materials. But in the 2000s it closed due to competition from Chinese suppliers. It reopened in 2018 and by 2022 it made up for 14% of global rare earth mining production.

In Europe, in January 2023, the Swedish mining company LKAB announced the discovery of the largest rare earth deposit in Europe. The news came as a relief to the region. However, its effective exploitation could take between 10 and 15 years.

There's a long way to go in reducing dependence on China. However, this is a priority, particularly in Europe, due to the fear that Beijing could use it geopolitical weapon and turn it into an instrument of leverage in the face of any future diplomatic dispute.

In fact, in December 2023 China banned the export of technology for processing rare earths, affecting any country that might try to develop refineries for these materials. Besides the veto, China limited the export on key materials such as germanium and gallium.

More for you

Top Stories