Did COVID take your sense of smell? A bionic nose may soon be able to help you

Not being able to smell properly is really annoying. Not being able to smell anything at all can actually even be dangerous!

According to Healthline, around 37% of people who have had Covid-19 experience some kind of loss of smell. For some, after a time, the function returns, for others, the inability to smell properly seems to be a lasting consequence.

Do you suffer from Anosmia? Anosmia is the inability to smell, a condition that has become more common since the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, Covid isn't the only cause; Alzheimer's, tumors, brain injuries, and several viral diseases can all cause people to lose their sense of smell. In the near future, a bionic nose may be the solution for those suffering from anosmia.

According to The Washington Post, 1-2% of Americans have difficulties with their sense of smell, a condition that worsens with age.

The newspapers also points out that globally, 15 million adults suffer from a loss of their sense of smell due to Covid.

Current treatment for people suffering from Covid-induced anosmia is limited, with just three options available:

- Wait and hope their sense of smell comes back by itself.

- Prescription steroid medication to reduce inflammation and speed up recovery.

- Attend smell rehab, where patients are exposed to familiar scents on a daily basis in the hope of restoring the nose-brain nerves.

However, two men may have come up with a solution that could offer new hope to patients suffering from anosmia.

Dr Richard Costanzo, a professor of physiology and biophysics at Virginia Commonwealth University and Dr Daniel Coelho, a specialist in otolaryngology, hope that their creation of a new neuroprosthetic, which they call a "bionic nose" will be able to help people around the world with this problem.

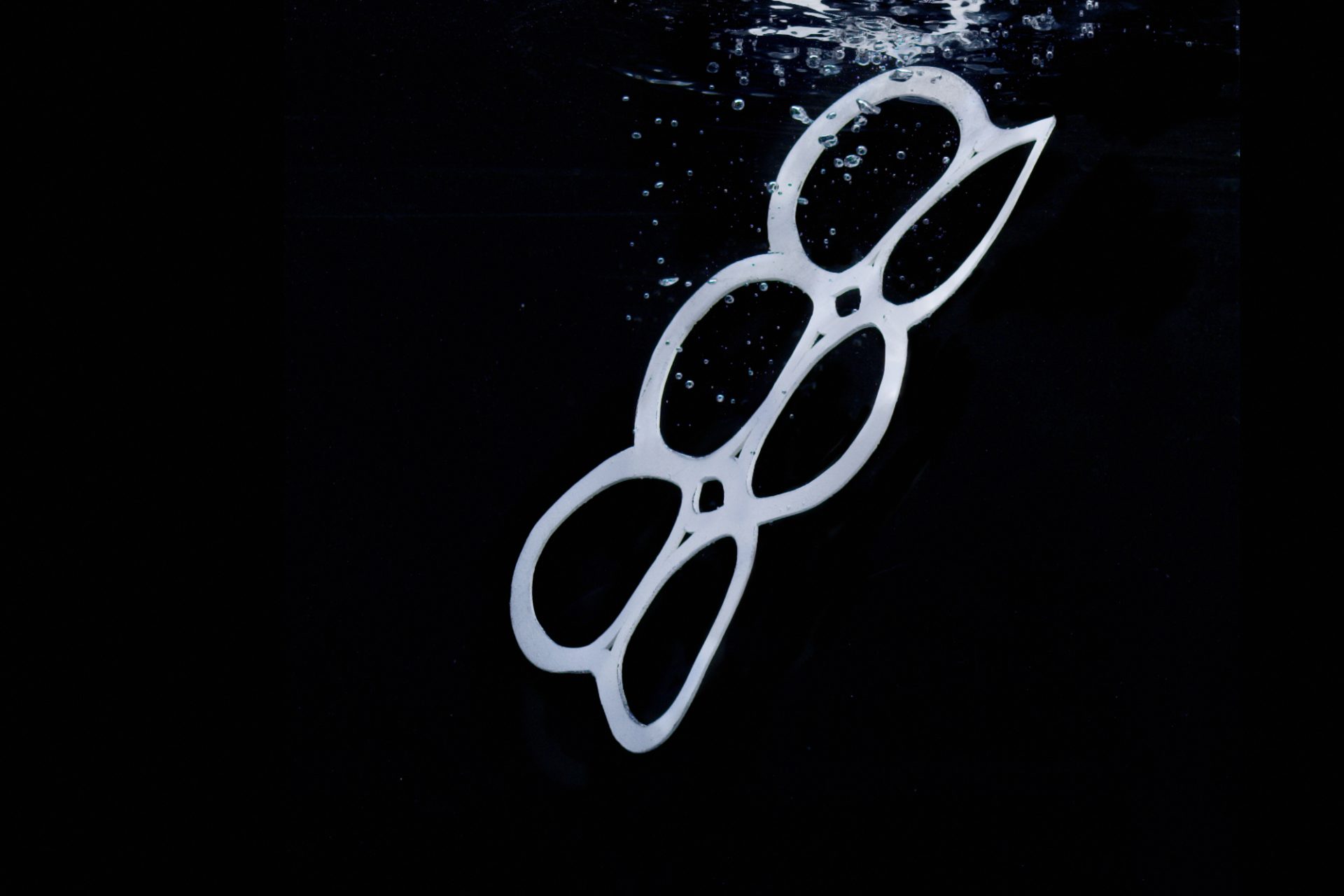

Photo: By Genia Brodsky and Noam Sobel (The Weizmann Institute) - (2010) PLoS Computational Biology Issue Image, Vol. 6(4) April 2010. PLoS Comput Biol 6(4): ev06.i04. doi:10.1371/image.pcbi.v06.i04, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16938376

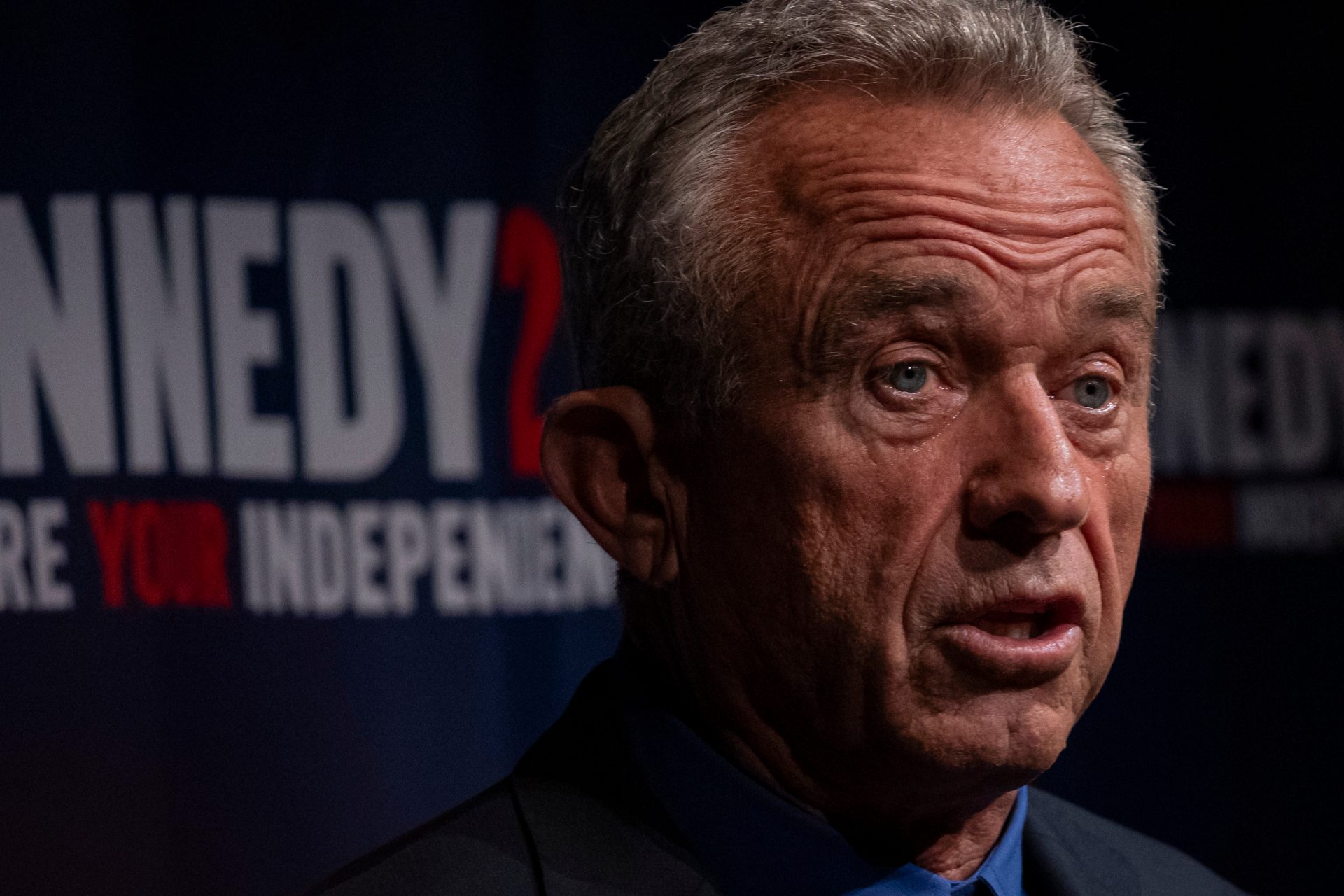

Dr Costanzo (pictured) has plenty of experience helping those with smell and taste problems. He was the co-founder of Virginia Commonwealth University's Smell and Taste Disorders Center, which was started up in the 1980s, a first in the United States.

Photo: Virginia Commonwealth University

According to IEEE Spectrum, following many years of research on smell loss and investigations into possible solutions, Dr Costanzo decided to begin exploring a hardware solution to help patients with a lack of smell in the 1990s.

Costanzo decided to work together with Dr Coelho (pictured) as he has plenty of experience with helping people with hearing loss through the use of a cochlear implant.

Photo: Virginia Commonwealth University

Costanzo told the Washington Post that the olfactory implant the duo are working on is based on the same concept used in the cochlear implant, which allows deaf patients to hear.

IEEE Spectrum reported that the duo began talking about the project in 2011 and concluded that a prosthetic for smell could be very similar to a cochlear implant.

Coelho told the publication, "It's taking something from the physical world and translating it into electrical signals that strategically target the brain."

By 2016, Coelho and Costanzo finally had a U.S. patent for their olfactory-implant system. They have been working with some talented collaborators to make this dream (which has become more urgent with the surge in cases of smell loss due to Covid) happen.

According to IEE Spectrum, the team includes "an electronic nose expert in England, several clinicians in Boston, and a businessman in Indiana."

Despite having a "dream team" working on the project, Costanzo cautions that this device still has a long way to go, the process of smelling is complex, and it will take time to get the device to work correctly.

Costanzo explained the Washington Post how our sense of smell works. He explained that we can smell due to specialized olfactory receptor cells in the upper part of the nose that can detect chemical vapors in the air.

This smell information is then sent by the cells through nerve fibers, which go through openings found in the base of our skull and then connect to the olfactory bulb located in our brain.

Photo: By Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator - Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustratorFile:Head_olfactory_nerve.jpg, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68370471

"The olfactory bulb shares this information with the rest of the brain, resulting in the perception of smell, such as the scent of an orange or fragrance of a rose," Costanzo told the Washington Post.

Costanzo told the WaPo that duplicating this sensory process is particularly challenging. "The problem with smell is that we don't know what physical properties of chemical odors are important for encoding all the different smells that exist," Costanzo said.

Electronic noses or e-noses already exist, and you probably have them in your home. A carbon monoxide detector is a common example of a simple e-nose.

However, the problem with these devices is that they cannot distinguish or detect very many odors, nowhere near what human beings can catch with their sniffer.

So Costanzo and Coelho have decided to bypass the damaged olfactory cells altogether in their prototype and instead simply stimulate the brain in a direct manner with an implanted electrode array.

A combination of microelectronic, computer processing and artificial intelligence have been used in their bionic nose to achieve this.

Costanzo explained to the WaPo how a tiny, external odor-detecting piece will send signals to a microprocessor chip generating "unique digital fingerprints for different smells."

Then the information will be sent by the chip through special radio wave frequencies to a receiver in the individual's skull, which will stimulate the areas of the brain that create "a particular smell sensation or perception."

The idea of a bionic nose helping people who suffer from a loss of smell is very exciting. Regardless, Costanzo doesn't want people to think this is something they will have access to in the immediate future, as it is a device that is complex and will take more time to perfect.

"I think we're several years away from cracking those nuts, but I think it's doable," Costanzo told IEEE Spectrum. There are plans to build a clinical prototype version soon, though. "Hope is coming," Coelho said to the Washington Post. "There are a few important things that we need to get into place, but there's very little reason to think that this device shouldn't work."

More for you

Top Stories