Gasping for breath in the world's worst toxic smog in India

Winter in Delhi brings with it a smog so thick, you feel like an extra in Cormac McCarthy’s dystopian “The Road”, except that you are far from alone.

The air has a yellow tinge to it and brings on bouts of coughing and wheezing and chronic chest conditions which doctors now openly attribute to pollution.

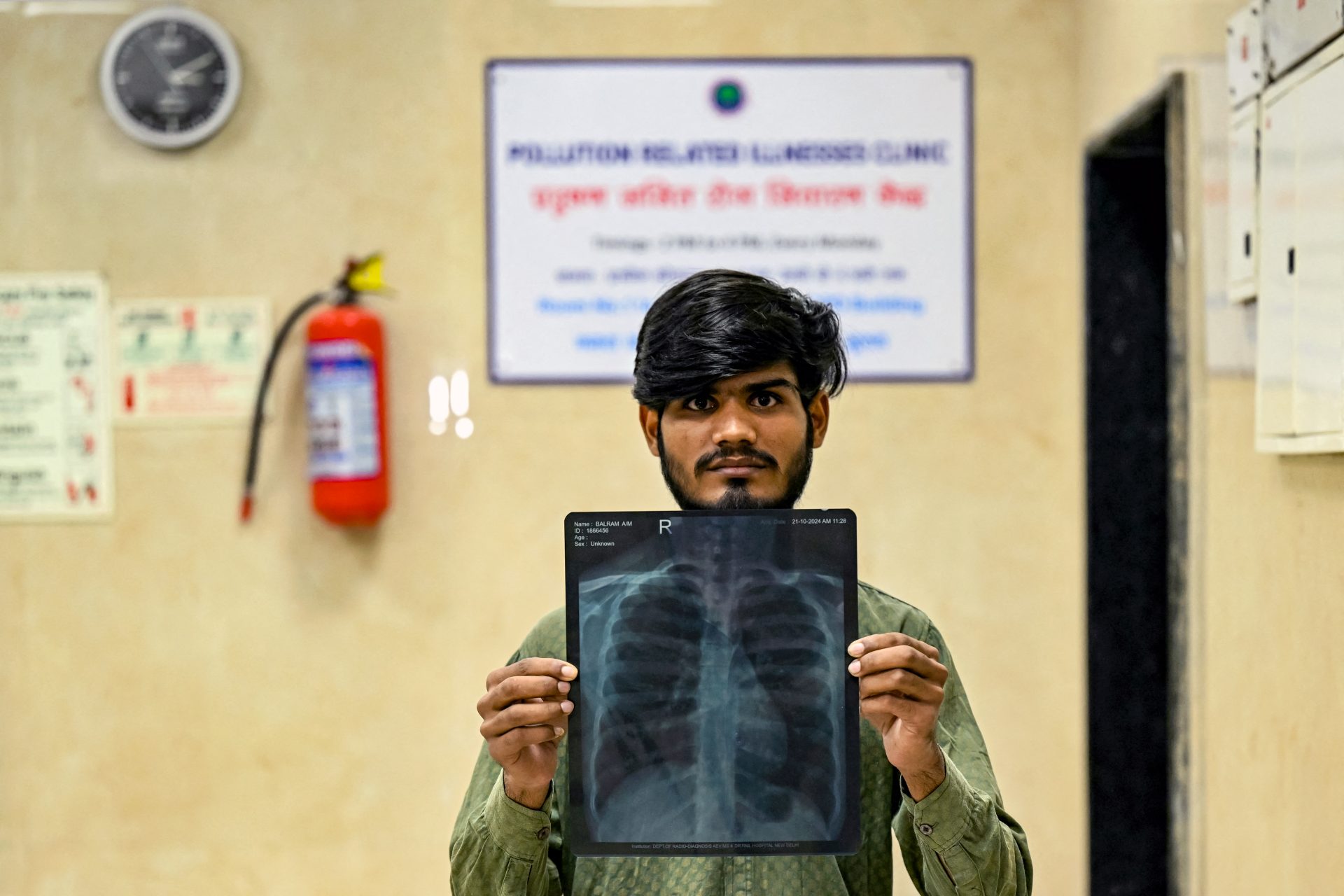

There are even special clinics set up in Delhi, dedicated to pollution-related illness, according to CNN.

The Decision Support System (DSS) for Air Quality Management estimates that traffic accounted for 16.4% of Delhi’s pollution on November 25, reports the Hindustan Times.

The burning of stubble on farms to the north and west of the capital accounted for a further 11%. Then there is the pollution from the brick kilns and factories that blows in from as far away as Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The contributory factors are exacerbated by the landlocked geography of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, reports the BBC.

The fact that this region is surrounded by mountains and lacks the kind of winds that can disperse the pollution results in a potent sulfur-colored soup.

As winter approaches, dropping temperatures trap this toxic haze close to the ground, resulting in Air Quality Index (AQI) measurements off the scale.

Four hundred and higher indicate a “severe” situation, but towards the end of November, the AQI soared to a staggering 1,743, according to The Financial Times.

Nowhere else on earth has air this dangerous to human health, say global air quality monitors; India has eight out of the 10 most polluted cities in the world.

“It’s impossible to breathe. I just came by bus, and I felt like I was suffocating,” Deepak Rajak, a patient at the air-pollution clinic, told CNN.

Deepak’s daughter Kajal Rajak added, “You can’t see what’s in front of you. We were at the bus stop, and we couldn’t even see the bus number, or whether a bus is even coming.”

Experts agree that aside from Delhi’s annual action plan which curbs industry and traffic at peak pollution times, a further year-round approach is vital.

“We need to work on systematic and comprehensive actions which reduce pollution at source,” environmental analyst Sunil Dahiya told CNN.

“This means that we have to start talking about how much is being emitted in terms of air pollution from the transportation sector, power sector, industries, waste and in which geography.”

But there is a notable reluctance to engage in the problem according to Parthaa Bosu, strategic adviser at the US-based Environmental Defense Fund, in the BBC. This, he says, is the biggest obstacle to finding a long-term solution.

More for you

Top Stories