This simple brain trick can improve your memory and boost learning

There are tons of hacks you can do to boost your learning capabilities and improve your mental health but few of them are as fun as the trick recently developed by researchers at Duke University.

Well, the trick isn’t really a trick per se but rather a change in your mindset. Researchers discovered that people who shift from a high-pressure mindset to one rooted in curiosity are able to improve their memory substantially.

Now you might be thinking to yourself: “How did the researchers even figure this out?” It is a good question and one that can be answered fairly easily when you look at how the researchers designed their study.

Duke University’s Alyssa Sinclair and Candice Wang recruited 420 adults to pretend as if they were going to be stealing valuable art for the day. The thieves were split into two groups, imperative and interrogative, and told to scout a virtual art museum.

Here it’s important to understand the concepts of imperative and interrogative as the researchers explained them in order to understand how different motivations in mindset affect our attention, focus, and memory.

“Imperative motivation links urgent goals to actions, narrowing the focus of attention and memory. Conversely, interrogative motivation integrates goals over time and space, supporting rich memory encoding for flexible future use,” the study’s authors wrote.

Sinclair later defied these groups in a much more understandable way when speaking with Duke University’s newspaper, calling them the urgent and curious groups as she explained how they were tasked with exploring a virtual museum for an art heist.

The urgent—or imperative—group was told to pretend they were master thieves that were committing their epic heist at that moment. They were tasked with stealing as much as they could at the moment as they roamed the virtual art museum.

Those in the curious— or interrogative—group were told something completely different and asked by the researchers to pretend they were walking the halls of the virtual museum in order to plan a future heist.

Once the backstories were established, participants began playing through the virtual heist. Each person was allowed to explore a museum that had four colored doors and behind each were paintings along with their value.

Some rooms held paintings that were more valuable collections of art than other rooms and the participants could earn real-life bonus money when they discovered a room that housed a valuable collection.

What the study’s participants didn’t know at the time was that there would be a memory recall exercise the day after they completed the computer simulation and it was during this exercise that Sinclair and Wang realized the difference in mindsets was significant.

Those in the curious (interrogative) group were much better at accurately recognizing all paintings in the museum but they were also at remembering their total values even if the paintings were not high value.

“The curious group participants who imagined planning a heist had better memory the next day,” Sinclair explained to Duke Today. “They correctly recognized more paintings. They remembered how much each painting was worth.”

In comparison, the urgent (imperative) group’s participants only remembered high-value paintings and the researchers concluded that the reward motivation while pretending to perform the heist ended up disrupting the memory modulation of the urgent group.

“Overall, we demonstrate that a pre-learning motivational manipulation can bias learning and memory, bearing implications for education, behavior change, clinical interventions, and communication,” the researchers concluded.

This study may seem silly but it does have real-world applications and ramifications for those attempting to improve their memory. The urgent group’s ability to recall high-value doors shows how certain modes of learning can be adapted to specific situations.

“If you're on a hike and there's a bear, you don't want to be thinking about long-term planning,” Sinclair told Duke Today. “You need to focus on getting out of there right now.” This is when an urgent mindset might be more appropriate.

However, Sinclair added that if you’re trying to show someone the consequences that could arise long-term from lifestyle changes then adopting a curious mindset might be a more effective approach.

“Maybe for that, you need to put them in a curious mode so that they can actually retain that information,” Sinclair explained.

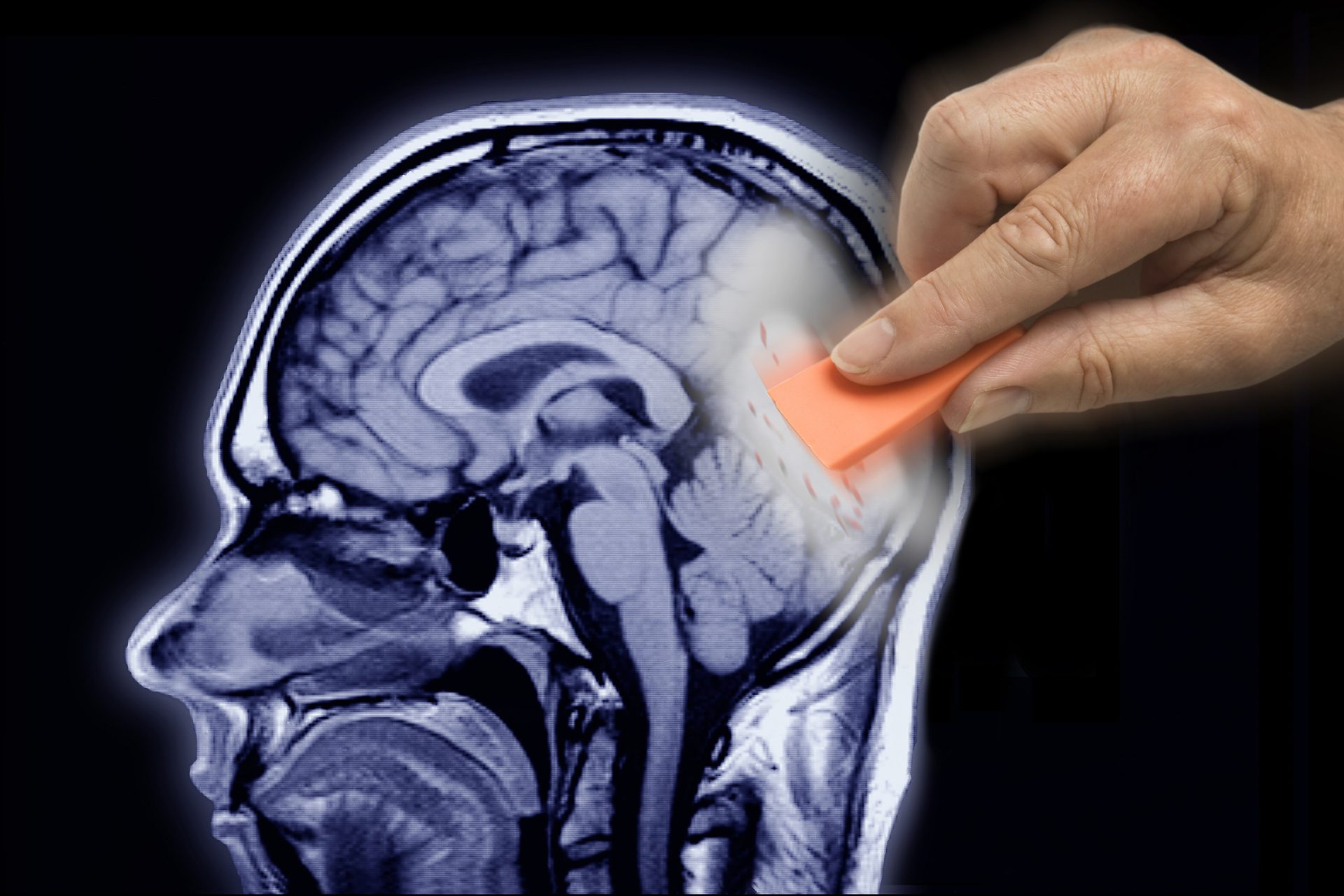

Duke today noted that Sinclar and Wang were following up on their research and were looking at which parts of the brain were engaged in each mindset. It seems that urgent mindsets involve the amygdala while curious mindsets the hippocampus.

More for you

Top Stories